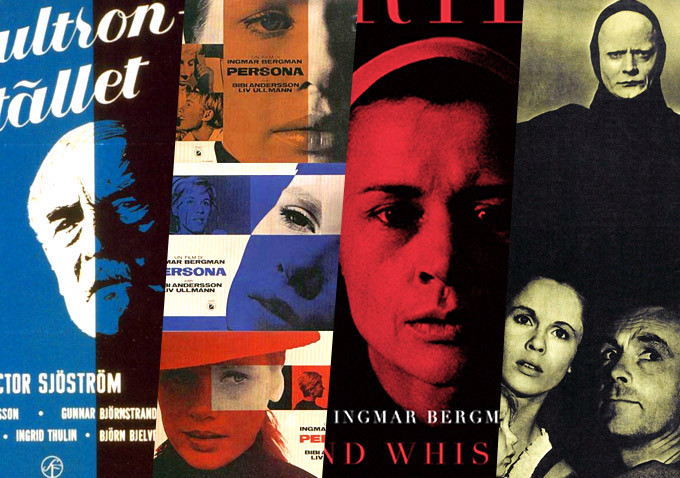

“Winter Light” (1962)

Anguish, anxiety and spiritual crisis are each front and center in Bergman’s “Winter Light” as well, but it’s replete this time with a stronger undercurrent of bitterness and cruelty. This severe and rigorous picture centers on an unraveling local pastor (Gunnar Bjornstrand) whose creeping doubts in God are beginning to show. Set over a three-hour period on a coldly inhospitable November afternoon, the preacher finishes his Sunday sermon and then is overwhelmed by the demands from members of his dwindling parish with their own needs. One man (von Sydow) is disabled by his own existential melancholia; his fears of China’s nuclear capabilities are paralyzing. Another parish member, a plain-looking woman (Ingrid Thulin) in love with the priest confesses her affection, further complicating and weighs down his personal turmoil. As such, the cleric cannot help his community and when set upon by an enamored school teacher, his resentment and contempt begins to seethe to the surface. Bergman considered “Winter Light” one of his favorite films, and it begins to break out of the constraints of the theatrically staged chamber drama thanks to full-time cinematographer Sven Nykvist, who masters a more aggressive and visceral style of framing: note how the framing renders the priest’s and woman’s long exchange as both interrogation and confession. Stark and marked by periods of uncomfortable silence (“God’s silence,” Bergman said) “Winter Light” is as austere a film as he ever made, but within its formidable confines resonates an exquisitely observed story of haunting, internalized suffering.

“The Silence” (1963)

On the surface (and beneath) one of Bergman’s most forbidding films, “The Silence” is the final segment, after “Winter Light” and “Through a Glass Darkly” of his “Faith Trilogy” (so-dubbed by critics —Bergman himself only adopted the term with reservations). But the film also prefigures many of the themes of “Cries and Whispers,” though here, Sven Nyqvist’s photography is in silky, insinuating black and white as opposed to the crushing reds of the later film, lending an even more austere edge to what is already an overtly formalist exercise. Two sisters, the ailing, intellectual Ester (Ingrid Thulin) and the sensuous, uncaring Anna (Gunnel Lindblom), along with Anna’s young son Johan, are making a journey through an unnamed Eastern European country, in which none understand the language (dialogue is minimal). They hole up for a few days in a hotel of crumbling grandeur, and as Ester contends with bouts of body-wracking pain and despair, Anna ventures out and has several sexual encounters, while Johan drifts between his sick aunt and the other hotel residents, most memorably a troupe of circus dwarves. There are several ways to interpret this curious, quiet, and often cruel film, but the sisters inevitably come to stand for two mutually distrustful, equally solipsistic halves of the same person —Ester the intellectual, who tries to find meaning in every occurence; Anna the flighty, earthy, selfish individual who engages in sex as meaningless as her worldview. What’s remarkable for the humanist Bergman is the cool dispassion with which he regards both women here, verging on distaste —instead little Johan is his proxy, and so the film becomes a kind of passive/aggressive battle for the boy’s unformed soul between the polar opposites represented by these two women, who are almost abstractions rather than recognizable human beings. Its subzero atmosphere makes “The Silence” hard to adore, but it’s what also makes the film impossible to forget.

“Persona” (1966)

Rhetorical question: what kind of filmography can, no matter the vagaries of fashion, always offer up a title that feels like it’s of primal importance to our understanding of who we are right now? With

its hard edge of experimentalism verging on science fiction, and its motifs of porous identity, consciousnesses and memory, step forward, “Persona.” This constantly astonishing, vital but boundless film stars Liv Ullmann as the actress Elisabet and Bibi Andersson as her nurse Alma, and unfolds as the strangest, plangent melody in which each note is deft, definite and clear and yet the whole makes unearthly, unfathomable, uncanny music. “Persona” tells the story of the recuperating

Elisabet being tended by the gregarious nurse Alma, but over the course of the film, the mutual reliance and occasional mutual antipathy of the relationship introduces a kind of static buzz into the background, increasing in intensity until, at a moment of controlled cataclysm, the women seem to conflate irrevocably. At least this “eclipse” sensation is one interpretation —there are many, as “Persona” can be deconstructed on just about any level and still not give up all its mysteries. It is also shockingly modern —from the flash-screen image of an erect penis that prefigures “Fight Club” by decades; to the avant-garde projector jam effect; to the reveal of Bergman and his crew filming; to the scenes of the boy watching the images of the women (in the famous straight-on/profile shot that no one ever made feel as unforced as Sven Nykvist). For any aspiring cinephile for whom Bergman’s reputation can seem daunting and stuffy, as though grown over with respectability and ivy, it is an astounding corrective; nearly fifty years old, nothing in “Persona” feel less than brand new today —it will all still be a revelation tomorrow.