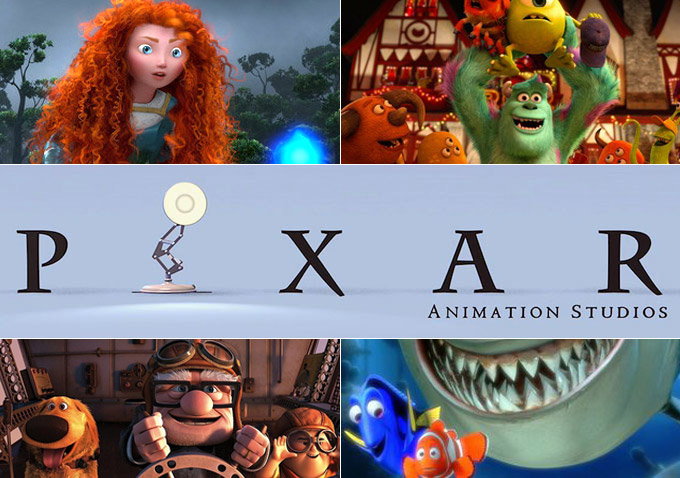

It’s hard to think of a studio more singularly adored than Pixar Animation Studios, the creators of “WALL-E,” “Toy Story” and “Finding Nemo.” Of course, they weren’t always everybody’s favorite. The studio started out as an experimental, computer-based component to George Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic effects house, one that Lucas had so little faith in that he promptly sold the team to Apple founder Steve Jobs, who looked at Pixar as a well to sell sophisticated graphics processors (the initial short films that created so much buzz and attention were supposed to serve as mere tech demonstrations). The artists at Pixar, however always had one clear goal in mind: a feature-length animated movie, groundbreaking in the same ways Walt Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” was way back in 1937. Pixar accomplished this (with Disney’s help) in 1995 with “Toy Story” and since then have gone on to achieve an unparalleled streak of critical and commercial success, amassing nearly 30 Oscars and almost $8 billion worldwide (they were sold in 2006 to Disney for more than $7 billion, so they’re finally making a profit!) But, contrary to popular opinion, they’re not perfect.

It’s hard to think of a studio more singularly adored than Pixar Animation Studios, the creators of “WALL-E,” “Toy Story” and “Finding Nemo.” Of course, they weren’t always everybody’s favorite. The studio started out as an experimental, computer-based component to George Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic effects house, one that Lucas had so little faith in that he promptly sold the team to Apple founder Steve Jobs, who looked at Pixar as a well to sell sophisticated graphics processors (the initial short films that created so much buzz and attention were supposed to serve as mere tech demonstrations). The artists at Pixar, however always had one clear goal in mind: a feature-length animated movie, groundbreaking in the same ways Walt Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” was way back in 1937. Pixar accomplished this (with Disney’s help) in 1995 with “Toy Story” and since then have gone on to achieve an unparalleled streak of critical and commercial success, amassing nearly 30 Oscars and almost $8 billion worldwide (they were sold in 2006 to Disney for more than $7 billion, so they’re finally making a profit!) But, contrary to popular opinion, they’re not perfect.

In fact, there are a handful of nagging problems with Pixar movies to date, that show some of the seams of their successes. And it takes someone who is obsessed with the studio and their films to even be able to point out these issues. It’s also worth noting that when Pixar started, none of the principles were, you know, filmmakers. For lack of a better word, they were technicians, working desperately to craft the new technology to fit their storytelling needs. This makes the studio’s accomplishments (especially early on) even more impressive and explains, at least somewhat, some of their shortcomings.

1.) A Lack of Strong Female Characters

1.) A Lack of Strong Female Characters

The most glaring (and frequently written about) problem with Pixar is their severe lack of strong female characters (yes, we’ll get to “Brave” in a minute). When Joss Whedon was brought onboard “Toy Story” to try to fix some major problems with the initial scripts (a three-week job that stretched into a four-month residency), one of his major additions was a strong female character, who would rescue Woody (Tom Hanks) and Buzz (Tim Allen) from the clutches of the sadistic neighborhood kid Sid. The problem was that Whedon’s character was Barbie, and toy giant Mattel, unsure of the “Toy Story” property (and about giving their beloved character a voice and personality that didn’t necessarily mesh with their own ideas) denied Disney and Pixar permission (the band of merry mutant toys replaced her). This negated the strong female character from “Toy Story” (Bo Peep is such a nonentity that by the third movie she’s been removed entirely) and set an ugly precedent of marginalizing female characters that the studio has mostly followed since then. Female characters appear in almost all of the Pixar movies, sometimes in prominent roles (like Dory in “Finding Nemo”) but few are what you would consider strong characters. Despite Ellen DeGeneres’ genuinely amazing performance, sometimes Dory feels less like a character and more like a plot device. There are, of course, exceptions, most notably in “The Incredibles,” in which Elastigirl (Holly Hunter), boils down the tenants of feminism into a thirty second speech she gives her daughter Violet (Sarah Vowell), while both are facing imminent death. Whedon, who in the years since “Toy Story” had become critical of the studio’s female characters, said that when he was watching this sequence in the theater, his wife leaned over to him and said that it had been written for him. Still, the female characters after “The Incredibles” have reinforced these bad habits, with many being defined solely by their male counterparts (like Jesse in the “Toy Story” movies) or disappearing from the movie entirely (Ellie from “Up” is a barely-seen narrative engine; Kevin the bird, however, is a woman). The response became loudest around the time that “WALL-E” was released, where the studio assigned outdated, binary sex characteristic to genderless droids.

The studio’s response, of course, was “Brave,” a movie that was set to be the studio’s first feature directed by a female filmmaker (Brenda Chapman) and described, at least initially, as the studio’s “feminist fairy tale.” The problem, of course, is that Chapman was fired 18 months before the feature’s completion, largely due to what she perceived as the studio’s glass ceiling and much of the movie’s female-positive message went along with her. Instead, the main character of “Brave,” Merida (Kelly Macdonald) was a feisty, independent woman who learned about selflessness but at the end didn’t seem all that strong; her “awakening” didn’t cause that much change. Also, whatever good came from the film’s presumed progressiveness was minimized when Merida was co-opted by the anti-woman Disney Princess brand (and we all know how well that went). This week’s “Monsters University” doesn’t try to fix the problem. Most of the female characters are reduced to a horde of demonic sorority girls (and a brittle dean played by Helen Mirren) although there is a moment when Mike (Billy Crystal) and Sulley (John Goodman) sneak into Monsters Inc. and see one of the scariest monsters, who turns out to be (shock!) a woman. Too bad there isn’t additional information about her and she doesn’t actually speak.

2.) An Emphasis On Story Means A Lack Of Texture

2.) An Emphasis On Story Means A Lack Of Texture

Pixar has an infamous “story first” approach to their movies in which any extraneous detail, if it doesn’t directly serve the narrative, is jettisoned into the deep recesses of outer space. When “Ratatouille” started to wander under the guidance of original director Jan Pinkava, with a complicated web of food-initiated flashbacks and dream sequences in which Remy (Patton Oswalt) would vividly visualize the taste sensations he was experiencing (pieces of which you can experience in the videogame version of the movie), he was removed and replaced by “The Incredibles” helmer Brad Bird. Maybe more tellingly, after Disney bought Pixar and installed John Lasseter as, essentially, the head of Disney creative, one of his first orders of business was to promptly fire Chris Sanders, whose “Lilo & Stitch” Lasseter found too weird and aimless. Sanders went on to have a wonderful career at DreamWorks Animation, where he made “How to Train Your Dragon” and this year’s delightful “The Croods.” “Lilo & Stitch” is the perfect example of a movie that Pixar would never make because it is all about the tiny details that fill up and expand a life, but have little to do with the story. Why does Lilo love Elvis Presley songs? What does one of the aliens cross-dressing have to do with anything else? You easily imagine Lasseter looking at the gorgeous, watercolor backdrops for “Lilo & Stitch” and saying, “So what?” In Pixar movies, character traits and narrative beats are exclusively produced to drive the momentum of the story forward (or double-underline some thematic concern) – there is, ostensibly, no fat on these movies.

The problem, of course, is that too much of this means that there is very little texture to the stories. “Cars 2,” which involves a labyrinthine plotline involving secret agent cars and an alternate fuel source that turns out to be deadly, is the best example of this: it’s all plot, to the point that nothing ever makes sense because every scene is so busy zigging and zagging to the next pressing plot point. As mentioned before, Dory, a character from “Finding Nemo” that was so indelible that some were predicting an Oscar nomination for DeGeneres (which would have been an all-time first), is really a functional plot device: she sees the boat that takes Nemo but has short-term memory loss (a character trait of the actual fish), so that keeps her from ever really aiding in solving the mystery. While the relationship between Ellie and Carl Fredrickson (Ed Asner) might be the emotional center of “Up,” their entire relationship is summed up in an admittedly beautiful, wordless montage, that isn’t exactly lousy with specific details about their lives together or apart. They fell in love, they had some troubles, she died. Does it still make you cry? Sure. But there’s also nothing to really hang your hat on. A half-dozen characters in “Ratatouille” feel like they never exist outside of the kitchen, every buggy character in “A Bug’s Life” is there for the betterment of the story, and never once in either “Cars” movie is an explanation attempted as to why this crazy cars-world exists. You know why? These “unnecessary” details would take away from the story, but give the projects so much more in return.

3.) Every Movie Ends In A Chase Sequence

3.) Every Movie Ends In A Chase Sequence

Like many of Pixar’s bad habits, the every-Pixar-movie-has-to-end-with-a-chase thing was started with patient zero: “Toy Story.” In that movie, Woody and Buzz are making a frantic attempt to reconnect with their toy friends before Andy and his family move houses. There’s a rocket and a radio-controlled car and the whole thing was absolutely exhilarating. So exhilarating, in fact, that the studio decided to use it as their narrative template for many, many future adventures. “Toy Story 2” upped the ante of the chase by having it set on an airport’s runway (the third film eschewed the chase altogether, which was a nice move); “Up” concludes with an aerial chase through (and over and around) a zeppelin; “Monsters Inc.” features maybe the studio’s most famous climactic chase – one involving a seemingly endless sea of doors. “The Incredibles” and “Ratatouille” both have elaborate chase sequences but are staged before the finale, while “WALL-E” has a race against time that spans the cosmos. “Brave,” for its part, features a similar time crush, but is set in the mystical Scottish highlands instead of outer space. It got so bad that New York Magazine’s Vulture blog asked Pete Docter, the director of “Up,” why so many Pixar movies end with chases, and this was before “Cars 2,” where the entire movie feels like a chase (and, of course, it ends with one – a race against time, no less). “Yeah, it’s definitely something you think about,” Docter admitted. “But just from a storytelling standpoint, you want to have a sense of acceleration, that things are getting faster and deeper and more intense, so that’s why you inevitably get to some physical thing, which really viscerally gets the audience going. But it’s always something we’re aware of. But you just try to make it as good as you can.” And “Monsters University?” Yep. This one involves a chase through the human world, in a sequence that more closely resembles an installment from the “Friday the 13th” franchise than anything from the Pixar world.

4.) The Problem With Multiple Climaxes

4.) The Problem With Multiple Climaxes

Usually multiple climaxes isn’t viewed as a bad thing, especially in the bedroom (eyebrows raised), but when it comes to Pixar movies, it’s a huge issue. This problem really started with the end of “Finding Nemo,” in which Nemo is reunited with his son and are about to swim back to their little part of the ocean when – oh no! – Nemo gets caught in a net and has to convince a giant school of fish to swim to the bottom of the ocean. The moment is meant to double-underline the idea that Nemo has, thanks to his interaction with the Tank Gang, learned about selflessness and the importance of teamwork, and it shows that Marlin has let go of his obsessive worrying enough to at least let his son figure out this problem on his own. It’s just one beat too many and it has come up again and again in the Pixar movies since “Finding Nemo.” This is most noticeable in “WALL-E,” which, like “Finding Nemo” and Pixar’s lone, unofficial live action feature “John Carter,” was directed by Andrew Stanton. At the end of “WALL-E,” climaxes seem to come so fast and furiously that they start to bump into one another, noisily colliding. You’d think that the climax would be our heroic robots EVE and WALL-E stabilizing, to a degree, the flailing Axiom spacecraft, which has been overruled by a villainous robotic copilot (this is that sequence where the ship is tipping over and the humans, formerly immobile blobs, spring into action). But then there’s the issue of WALL-E being mortally wounded (or whatever the equivalent of a robot being mortally wounded is) and the desperate race back to a post-apocalyptic earth. What’s even more outrageous is that the movie doesn’t end there – EVE still has to fix WALL-E, which creates another added dip in an already dizzying rollercoaster of emotion. “Monsters University” suffers similarly (spoiler warning for those of you who care), with the movie seemingly culminating in the final round of the Scare Games, where Mike and Sulley are finally sized up for the monsters that they are. But wait! There’s more! The aforementioned chase through the human world happens after the end of the scare games, and that sequence has its own little climax, where Mike and Sulley have to scare a bunch of law enforcement officials who are after them. It goes on and on and on, with diminishing returns in terms of emotional payoff.

5.) Buddy Movie Overload

5.) Buddy Movie Overload

Again, this is a trait that started with the very first “Toy Story,” which was fashioned after mismatched buddy movies in the tradition of “Midnight Run” and “48 Hours.” At the time, this seemed downright revolutionary – the original “Toy Story” was released smack dab in the middle of what’s commonly referred to as the Disney Renaissance, with big, brassy, Broadway musical-esque animated epics. By comparison, “Toy Story” was small and character-focused. The songs that Disney suggested be in the movie weren’t the centerpieces of grand musical numbers, they were quietly played in the background of highly emotional scenes (by the third movie, this too had been abandoned). It’s just that this formula often became too formulaic. After “A Bug’s Life,” which was an attempt at building a kind of “group” dynamic, and the second “Toy Story,” there was “Monsters Inc.,” a buddy movie between two monsters. Then there was “Finding Nemo,” which didn’t seem like it was going to be a buddy movie but then turned into one (this time with two fish). “The Incredibles” was a different beast altogether and almost shouldn’t be talked about in the grander context of the Pixar oeuvre. “Cars” was a buddy movie about two mismatched cars, one that is interested in the excitement of the race and the other who takes in the quieter moments of life, while “Ratatouille” was a buddy movie about a rat and a chef (you can’t get much more mismatched). “WALL-E?” Buddy movie with two robots. “Up,” while it has more of a group dynamic if you count Kevin the mythological bird and Dug the talking dog, but it’s really a buddy movie between a roly poly Wilderness Explorer and the old man who’s been squared off by age. Even “Brave,” which promised to break all the rules, ended up being a buddy movie between a princess and her mother, who has been mistakenly turned into a giant bear. At this point it has become very apparent that Pixar knows how to make buddy movies, but at a certain point it goes from being a trademark to being a creative crutch, one that should be taken away from them. From the sounds of it, the next movie, “The Good Dinosaur,” will be a sort of buddy movie between a dinosaur and a young boy, but it should be impossible to shove the formula into the one after, “Inside Out,” which takes place inside the mind of a young girl. Right?

You could argue that the abundance of sequels is one of the worst things about Pixar, but that is less a trait of the films and more a product of the corporate culture. From what we understand, for every bizarre, high concept oddity that the studio is hell bent on producing, like Lee Unkrich‘s movie that takes place on the Mexican Day of the Dead, Disney is demanding a sequel, prequel, or spin-off from a preexisting property. So yes, another “Toy Story” is likely, and “Finding Dory” has already been scheduled for 2015. It’s a strategy that has served DreamWorks Animation quite well and is probably the pay off for some of the studio’s more adventurous upcoming projects. There also seems to be a lack of diversity that is reflected in the ethnicity of most of the characters on screen (although, again, “The Incredibles” featured both African American and Latina characters and the kid in “Up” is vaguely Asian) and the kind of stories Pixar is willing to tell. But look for that to change too, in the coming years, with new animators and experienced vets both wanting to branch out to tell deeper, darker tales. As always, the sky’s the limit for Pixar.

Danny: Highlighting the need for a push for diversity and better representation is snobbiness? O….K. You also mention the details/depth within Pixar movies being in the differentiation between characters… Please refer to plenty other articles that show that almost every female character in Pixar movies "has basically the same face"… No points for guessing the race, age and general aesthetic qualities of that facial type. (I say all this as a frustrated Pixar lover btw!)

While I am a Pixar enthusiast, I can say while I did not care for the article personally, I will say that it did give me quite a bit of critical thinking that I will apply for the future.

Still, bugs me that the author called Brave a buddy film; no, it is a tale between mother and daughter, not a story of two bros getting along the plot.

Whoever wrote this article is a complete moron. And has no clue about good film making and story.

"in which Nemo is reunited with his son and are about to swim back to their little part of the ocean when…"

Nemo is the son!!!! Marlin is the dad…

Everybody is entitled to an opinion, of course, but the facts on Pixar's founding are factually incorrect. The Lucasfilm Computer Division was never part of ILM, and ended up spinning off DroidWorks as well as Pixar.

It's true that Mattel didn't want Barbie in the first Toy Story. Back then they wanted her character to remain a tabula rasa for little girls. (They obviously later changed their minds.) There was a cute bit where she was going to screech into Sid's bedroom in her pink Corvette and tell Woody, "Come with me if you want to live." That's not a "strong female character", it's a "Terminator" reference. She wasn't going to have a lot of screen time in any case. In the end it was a blessing that Mattel denied permission, because it would have taken the solution to Woody's problem out of his hands. That's a Deus ex Machina, and very unsatisfying. The ending as produced is much stronger.

I think the author gets a little desperate to shoe-horn in the idea of everything being a buddy movie. WALLâ¢E was a love story. Calling Merida and Elinor "buddies" is also kind of a stretch. And the director switch on "Brave" was not due to any kind of glass ceiling. I'm not at liberty to say what it was, but that certainly wasn't it.

The kid in "Up" is "vaguely Asian"? He's modeled after a totally Korean guy, and voiced by an Asian kid. I really don't know how much more Asian the writer wants him to be.

Pixar makes great movies for kids and adults. This article is just trying to nitpick tiny aspects of future children's classics. I guess I can't blame a site called "Indiewire" for creating such hipster bullshit. Article's author should stop the "I don't like it because it's mainstream" stuff, and go back to waxing his moustache and cuffing his jeans.

My favourite Pixar film is by far 'The Incredibles', which is my way of saying I don't care for most Pixar films.

I dislike Pixar because:

–They love themselves too much. They, (particularly La$$eter,) constantly brag: "oh, we're the best studio in the world, and only we can put out the very best entertainment, blah, blah, blah…" And then they put on stuff like Cars 2. I have no respect for that.

–Pixar is hypocritical. They first blame Disney Feature Animation for churning out sequels mindlessly, but then they end up doing the same thing.

–Lack of women/females presence annoys me. They end up dead (UP, mom in Finding nemo) are Suzie homemakers (Toy Story 1, 2, and 3) powerful but man-reliant entities (Bug's Life, Ratatouille) or just plain morons (Finding Nemo.) Elastigirl breaks the mold, however, even though she is a bit on the Suzie homemaker side. Women are highly objectified; in the short Night and Day, a bunch of bikini clad Vegas women are howled at, as if we were still living in the 1940's.

–Widespread hatred of preteen/teenage girls. Is it just me, but do you get the feeling like Monsters University was made a prequel and not a sequel just so they could avoid showing Boo's 13-year-old self? The teen girls abandoning Jesse in TS2 portrayed girls getting involved in makeup as almost as bad as death. Young girl in Finding Nemo was a brat. Girl in Up grew up and died in the first 10 minutes of the film. I'm going to bet 20 dollars that the girl in Inside Out is going to have mood swings that the masculine emotional entities have to work around.

–No musicals. In Aladdin, Mulan, Beauty and the Beast, there were songs I could sing to. While Toy Story had some good songs, everything else was just jazzy, instrumental blahhh.

To the author of this article: I would like to see another article addressing some of these Pixar issues. They are present in all their movies. They annoy me greatly.

Also, how about a lack of truly memorable antagonists? Yes, nearly each film has a "bad guy" but there haven't been any characters in the Pixar canon (save for maybe Kevin Spacey's imposing Hopper from "A Bug's Life") who really stand shoulder to shoulder with the iconic Disney villains like Malificent, Scar, Jafar, and others.

Of course, Pixar's villains are much more complex than pure evil, and credit must be given there, but nevertheless, none of their villains are nearly as memorable as what Disney at its best has concocted.

Pixar makes movies not for kids, but for parents looking for wholesome products for their kids. Mystery and "disturbing" content, which children love, and which animates traditional fairy tales, are nowhere to be found.

The fact that young kids will eagerly consume these denatured market-measured fantasies is not proof of their excellence or even their market acumen, any more than the popularity McDonalds with kids proves it's great food. Despite the producers' best efforts, the Pixar movies retain an element of mystery, because of limited child comprehension and visual aesthetics which appeal to kids. But kids don't see the same movie adults do. Even the most literal plodding storytelling is mysterious for 6-year old.

so basically because pixar has a formula which is common in some of their movies (for every point you made, you had quite a few exceptions), it's bad filmmaking? These movies still make you laugh and cry and excite you. Yes, there are a few bad ones, but there's nothing wrong with finding a formula that works to get audiences excited, and sell tickets and merchandise (it is still the evil disney afterall)

Okay maybe I am in the minority here but the worse things to me about Pixar is their artwork. I find the Pixar characters to look like the siblings of a cabbage pad kid and a garbage pail kid. I don't want animated movies to look like two hour ads for toys 'r' us. Weak female characters or not I'll take classic Disney or Studio Ghibli's beautifully drawn and animated movies over Pixar's plastic, dopey, googly-eyed looking computer animations any day.

Thank you for the article. Good to know I'm not the only one who isn't impressed at everything Pixar throws out.

Thank you Danny. Totally agree.

Also, blaming Pixar for things out of their control (such as commercial marketing) is unfair – that is a problem with Disney's marketing wing surely? This is a big problem in the article, especially when you call John Carter an 'unofficial' Pixar film. Is Mission Impossible 4 also a Pixar film because Brad Bird directed it? Pixar artists may have contributed, but the film itself is down to its director and screenwriters. The big problem with the film was the poor use of flashbacks, which on DVD features is revealed to be something Stanton wanted to use in Nemo but Pixar stopped him. So if anything, it shows how the working atmosphere in Pixar is better than outside it.

A terrible article that misses so many of the great things in the films. You talk about the 'double' endings for Finding Nemo, but it is simply an end to the plot and then a conclusion for the characters. So yes, they find Nemo. But then we have a scene which underlines the character growth of each character. Same with Wall E – they save humanity, but then it goes back to what the film is really about: the relationship between Wall E and Eve and how compromising their 'objectives' for each other has bought them together. Other than Toy Story and Monsters Inc, I think its really unfair to call every film a buddy movie – pretty much all movies involve relationships with some key characters so could be boiled down to this if your being reductionist (which this article is throughout). As for female characters, there is a point in saying there are few strong LEADING female characters, but many of their films include female characters who play key nuanced roles (Dory being one which you unfairly dismiss precisely BECAUSE she carries much of the plot).

The fair points you make need more clarification, but are more worthy of discussion. For example, Pixar do seem less willing to have a film with a less perfected feel like Lilo and Stich (although that film itself has several problems), and this often results in over-reliance on action – which in the contexts of most stories only really translates realistically into chase sequences. Still, I think this shows how they are willing to raise the stakes in their films and that again it is unfair to define any 'race against time' scenario as a chase sequence.

These are movies for children. I think this article is a bit silly. Why would children's movies need more complicated plots and such. Besides, its seems that this awful, formulaic approach is really cleaning up at the box office.

This is the problem with "educated" "critics": they think they "know" things.

The Pixar issues with women is long standing. When Toy Story 2 came out in 1999, they did not have a Jessie doll for that Christmas season. They had a new Buzz Lightyear. They had a Woody doll dressed as Santa Claus. No Jessie on the shelves.

"Snow Whit and the Seven Dwarfs"

Whit?

If you don't care about your writing, why should we?

Wow, those are a lot of forced points. I would argue that most of your "worst" things about Pixar are actually strengths (except of course the lack of strong female characters. Brave and the Chapman story broke my heart). Most of your points are easily refuted, and as mentioned, are forced. For instance, your definition of "buddy" movies is really, really, really broad. If "Wall-E" is a buddy movie with robots, then "When Harry Met Sally" is also a buddy movie (in which the male and female protagonists end up having sex).

Sorry but what a piece of s***!

This article has clearly been written by a woman. Much of it simply doesn't hold water.

Just what I needed, more Pixar hate.

I'm starting to see why they called the '20's-50's the Golden Age of Film: There were no bigot Internet biggots bloggers like you.

Wow, posting an anti Pixar article on a site full of Pixar fan boys? You are a braver man than me. Be sure to lock your doors and windows tonight.

(all jokes aside, this is a great article, really)

The #1 problem with Pixar? They're not Studio Ghibli.

it's as good a day as any to find something to bitch about.

I completely agree with Danny below. It is especially obvious that #2 on this list is a stretch and insult to the studio. No room for texture? Give me a break. That is like saying 'Its bad to write great stories with themes that connect… I don't know how, but I'll find a way to talk about what could possibly lack from it!'

Jesse from Toy Story is a great female character. She has an interesting backstory and is not defined by anyone else. Also, Barbie from Toy Story 3? She was pretty awesome.

Good article. I liked authors points at #2, but I'm seriously shocked about Lasseter firing Chris Sanders and hating "Lilo & Stitch" – that was dissapointing to read…

And I don't find this article anti-Pixar, it's just the dose of criticism that even the best needs, in a way it proves how complex and debatable their works are. And it's better then your usual "hey it's new Pixar, it's gonna be great!" article.

I don't have much to say about the article, other than to address point #5 slightly.

It's really a stretch to call Brave a buddy film. Yes, a relationship is strengthened between two people, but if that is your definition of a buddy film, then a lot of movies are buddy movies. Same goes for UP which seems like more of an father-son dynamic than a buddy dynamic. I'll admit it starts as a buddy film between a grouchy old man and a spry kid, but it quickly becomes a father-son dynamic.

I also have to wonder, would you launch the buddy film critique against Howard Hawks? Aren't most Hawks' best films like Only Angels Have Wings, The Big Sky, Gentlemen Prefer Blonds, and Rio Bravo all buddy films? Most of his other films even carry a buddy film sensibility without being buddy films. Even in His Girl Friday and Bringing Up Baby, the romantic interactions for much of the film are constructed as buddy-like interactions. Was Howard Hawks just a hack repeating the same formulas over and over again? If you want to critique Pixar for reproducing the same themes, you need to be more explicit about your objections – what exactly about returning to the same theme don't you like? Because saying that they are just rehashing the same theme seems like a weak objection.

I'm sorry. But i justed wasted time reading an article i thought was going to be constructive and good. Instead i found myself reading an article that makes me wonder if the author just picked out small details, enlarged them to a ridiculous exaggeration and started mentioning "wrong things" just to complete this so called list.

I really agree with "Danny" here. The examples used in this article don't even make sense. On the contrary, the examples show positive things Pixar do. Like the mentioned Tuna-scene in Finding Nemo. What makes Pixar the absolut best at what they do are the subtle and not overexaggerated messages that get through if you read between the lines. It's strange just comparing Lilo & Stith to Pixar movies. While Pixar movies connect with people of all ages(trust me, i've seen grown men cry to Pixar movies), Lilo & Stith and most of Dreamworks animated films(Except How to Train Your Dragon) are a lot more interesting to kids. The really obvious and exaggerated messages and character-storys might work for you, but not for me. There's no challenge in watching a movie where everything is explained, where there's nothing for you to fill in using your imagination.

Another Pixar movie must be coming out. Time for another Pixar hit piece. Pixar-hate is certainly fashionable these days.

Agree with both Danny and Rudy.

I could care less about the female empowerment crap! Disney inundated us with Disney Princesses for 20 years! So much so that they now have their own brand! So what's wrong with doing movies that don't feature some spunky heroine looking for independence or dating monsters?? There are other stories out there that can be told! And Pixar has done them very well!

This article really shows the snobbiness of some of the writers at Indiewire.

Monsters University is a a sequel to a movie starring two male characters, of course the leads are going to be two male characters. A Bug's Life, Brave, The Incredibles, Wall-E, and Finding Nemo all have main-female characters or female leads, and, in my opinion, they are all strong females. The removal of Bo-Peep didn't start any trend of marginalizing female characters. Bo-Peep wasn't a very interesting character to begin with and she wasn't too useful. It sounds to me like you are looking for a parallel between the marginalization of women in society and the marginalization of women in Pixar, but the problem is Pixar doesn't marginalize women.

I have no clue what you are saying when you say every movie ends in a chase sequence because that simply isn't true. I think you are mixing a chase sequence up with an acceleration in the action.

I think it is ridiculous to complain about an emphasis on story. An emphasis on story is the reason why Pixar is the best at what it does. The texture is seen in the stark differences between the characters. It looks to me like you want extraneous detail for the sake of extraneous detail which would only distract viewers.

The problem you state about multiple climaxes isn't really a problem at all. The action that follows a could-be ending in Pixar movies always contributes to the movies overall message and plot. That can be seen especially in Finding Nemo in the scene with Nemo saving the tuna. That scene shows that both Nemo and Marlin have grown and there is a newfound trust between them.

Pixar makes animated movies that are made for children with stories suitable for all ages. In children's movies one theme has to be either family or be friendship. I haven't seen a children's movie that doesn't feature friends or family because those are two of the few things children can relate to. The Incredibles and Brave feature family while most of the rest feature friends.

Personally, I hate their art style. Those huge bulging eyes are the stuff of nightmares (uncanny vally) & the over-the-top facial expressions get on my nerves quickly.