Mentioning Vulture critic Bilge Ebiri’s positive review of Romain Gavras’ “Athena,” Schrader said that he took issue with praise levied toward the film’s long takes. “They’re not, in fact, long takes but full of hidden splices and stitching,” Schrader said, declaring the era of the long take — once distinguished by films like “Touch of Evil,” “Goodfellas,” and “I Am Cuba” — to be over.

“It’s now possible for anyone to stitch together these takes,” he said. “That notion of technical achievement as an arbiter of artistic achievement no longer means as much.” Schrader expressed similar sentiments toward cinematography as a field, suggesting that those eager to replicate Darius Khondji’s style could generally determine the approach he took, do what was absolutely necessary on set, and figure out the rest in post-production. The “post-world,” as Schrader described it, presents opportunities to “recompose in post,” given that images captured by an 8K film camera are of sufficient digital depth to pan around without loss of quality.

As the hour-long talk drew to a close, Schrader spoke about his planned next project, about a female trauma nurse in Puerto Rico. “I’ve just started on the second draft,” he said. “It’s this character I’ve dealt with over the years, but it was time for him to pull out a skirt. I wanted to write a female version, which changes virtually everything when you’re talking about sexual repression, guilt, and frustration. All sudden, you see it in a female context.”

Schrader expressed optimism that he’ll get to direct this next project, though he’s more cynical about the future of filmmaking as a whole. “As I said to Martin Scorsese when he was talking about preserving film, ‘Why should we preserve film when we can’t preserve the people who are going to watch it?’ That’s the long-term answer.”

A few additional highlights from the Paul Schrader talk were as follows:

On writing the first draft of a screenplay: It ideally should go very fast, and it should not be that long. If you can tell a story at 70 pages, it’s going to work at 90. Just get it out there. Let it go. When a young writer says to me, ‘“I want you to read something, I don’t think it’s very good, but I did it last week,” let me see that. A writer comes to me and says, “I’ve been working on this thing for three years. Will you read it?” Ugh.

On how to proceed from that point: Get that first draft out there, and you know there’s another level. Think about it, figure out how to get it up to the next level. But when you start moving into a third draft, if you haven’t gotten there yet, something’s gone wrong. Third draft: you need to clean up things, improve some dialogue, improve this scene. But if your architecture isn’t in place after two drafts, you started writing too quickly.

On retaining creative control: When you have the final cut, the only approval you really need to get is from yourself. I remember that feeling while shooting “Mishima” in Japan. I’d realized the financing of that film was very odd, and the people who’d financed it were claiming they weren’t financing it for political reasons in Japan. And Warner Bros. was involved, but they didn’t care about it; they were doing a favor to George Lucas. And so I realized, “Nobody financed this movie, so I can do anything I want.” And then an enormous weight descended on me because there was nobody to blame.

On when composers become involved in his filmmaking process: “Mishima” was an exception because Tom Luddy, the producer, had been involved with “Koyaanisqatsi,” so he knew Phil, and Phil had done three biographical operas — “Einstein on the Beach,” “Satyagraha,” and “Akhnaten” — so we approached Phil as doing it as an opera. He said he scored the film from the script, then rescored it from the cut.

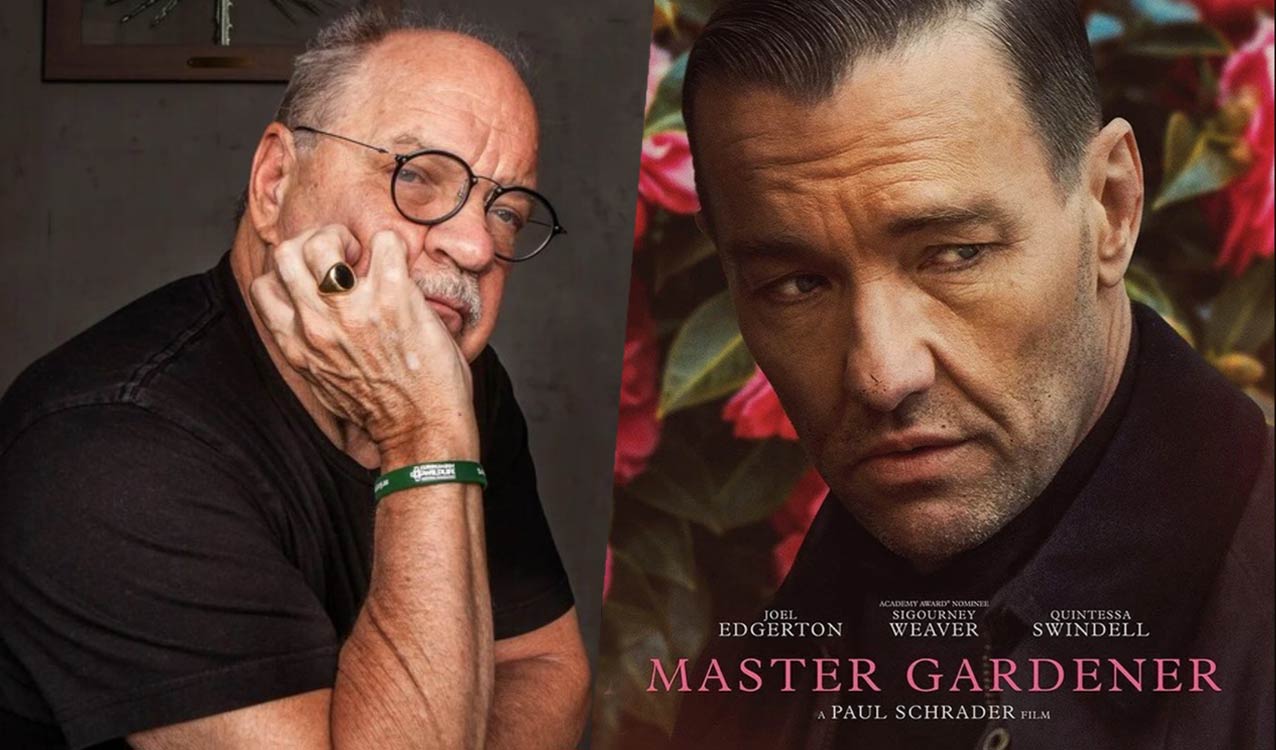

Other than that, it usually starts to occur to you somewhere while you’re shooting. On “Light Sleeper,” with Michael Been, I thought, how about another voice for this character? He has a dialogue voice, he has a duration voice but give him a third voice, which is a singing voice. With “Master Gardener,” with Dev Hynes, was interesting; I was drawn to him, because he is a wunderkind. He does everything: jazz, rap, Blood Orange, and classical. He hadn’t done much electronic, which I thought would be interesting. It ended up being a stressful situation because he wasn’t working where he was most comfortable. He was most comfortable on the piano, not most comfortable just working purely electronically.

It’s interesting when you get new composers. I started with Jack Nietzsche [on “Blue Collar” and “Hardcore,”] did the second two [“American Gigolo” and “Cat People”] with Giorgio Moroder, and eventually went over to Scott Johnson [“Patty Hearst”] Dave Grohl [“Touch,”] and an electronic composer [Michael Brook] on “Affliction.” Michael Been was on “Light Sleeper,” and it was his son on “The Card Counter.” When you get new people, it’s always interesting, but you’re working. If I hire a veteran composer, which I did once and regretted, you get their greatest hits. If you present them with a problem, they’ve solved it two dozen times already. They know exactly the solution and its permutations… If you give it to a young composer, you get interesting work, but it is labor-intensive because you end up spending time with them.

Reflecting on his “Venezia 70 Future Reloaded” trailer ten years later, and why he’s wearing a fluorescent green bike helmet on the Highline in it: It was probably the only [color] we could get. What I did was stick all kinds of GoPros all around because we were entering at that time the era of Multicam minicams, which now more and more were the high quality of small cameras. Tony Scott used to line up six 35mm cameras with different lenses. More and more, you see films being shot with ten cameras: just take a camera, stick one up there, put one over there and see what we get. And that changes. It also changes the other way, which is to be monastic about it: let’s use one camera, and let’s cut in the camera. The other approach is to be scattershot: let’s shoot everything, throw it into the editing room, and make a run for it.

And on that trailer’s interpretation of the future of cinema: Obviously, a lot of great films are being written in Ukraine right now, but you can’t make them for another five years. You can’t. And we have been in a revolution of what a movie is. It’s hard to make a movie when the definition keeps changing. Is “Mad Men” a movie? Yeah, I think “Mad Men” is a movie. Is that YouTube clip about a cat stuck in the door a movie? Yeah, that’s a movie too, and so is everything in between. To be judgmental, we used to say a movie is 90-150 minutes long, and it takes place in a darkened room with a projected image. That’s just totally not true anymore. I see people watching movies on their phones in the subway; the first time I saw it, I thought, that’s weird. Then, I realized that it’s not weird anymore. Everybody’s doing it.

On whether film audiences can be recaptured, and why Marlon Brando was right: Movies had a hegemony for many decades on audiovisual experience. They don’t anymore. In fact, they’re almost competitive with video games and all the other forms of audiovisual entertainment. There were decades where, if you wanted to see audio-visual entertainment, you had to go into a dark room with a bunch of other people and see an image projected against a wall. That’s never going to come back again. And the multiplicity of audiovisual experience is only going to continue to fracture as we get closer to the multidimensional virtual-reality cinema. Bruce Willis just licensed his image for deep-fake technology, so his family will keep getting money as he does commercials with deep-fake. The first time I ever heard about this, I was working on a script 20-30 years ago with Marlon Brando, and he said he’d just been with someone who’d had his face scanned. And I said, “Why would you have your face scanned?” He said, “For the commercials, of course.” Marlon was way ahead of the curve on that one.

“Master Gardener” is currently seeking distribution. Paul Schrader’s NYFF60 Talk was organized by Talks co-programmers Maddie Whittle and Devika Girish.