Paul Schrader always knew that “Master Gardener” would be controversial.

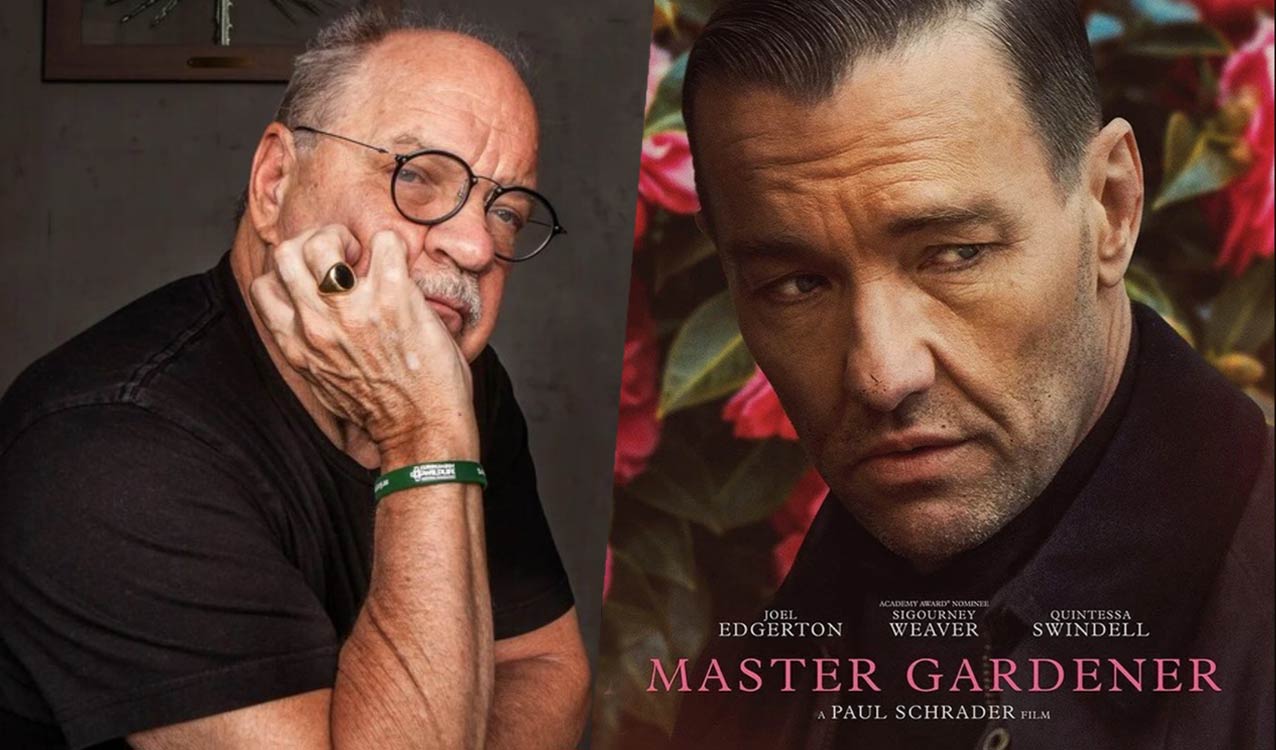

In the legendary filmmaker’s crime-thriller, which had its North American premiere at the 60th New York Festival earlier this month, Narvel Roth (Joel Edgerton), the head horticulturist of a historic Southern estate, is tasked by its demanding owner, Norma Haverhill (Sigourney Weaver), with taking on her grand-niece Maya (Quintessa Swindell) as an apprentice, only for Roth’s past in a white-supremacist movement to come to light.

READ MORE: Paul Schrader Says His Next Film Centers On A Female Trauma Nurse In Puerto Rico

“Basically, [“Master Gardener”] lets one of the most villainous characters in our current culture — the white supremacist — kind of skate [by,] because it aligns him with other characters I’ve written who are defined by their occupations, be it a taxi driver, a drug dealer, a card player, or a gardener,” Schrader said, speaking at the 75-capacity Amphitheater inside Lincoln Center’s Francesca Beale Theater during a free, open-to-the-public talk held the Sunday following his film’s Main Slate premiere.

In conversation with filmmaker and NYFF program advisor Gina Telaroli, Schrader said that “Master Gardener,” which made its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival in September, has thus far engendered less controversy than he thought it might, given the premise. Schrader had been especially bracing for blowback given that Roth becomes romantically involved with both Norma and Maya, which adds another layer of emotional, eventually existential complexity to the drama in keeping with Schrader’s recent, late-career works “First Reformed” and “The Card Counter.”

“I was a little concerned about the May-December [dynamic] and that, because of political correctness, people were gonna buzz me about this guy having a romantic affair with one woman old enough to be his daughter and another one old enough to be his mother,” Schrader said.

“And so I thought, ‘Well, maybe we can dodge that Lolita thing by making him a Proud Boy,’ because then people’ll get so f—ed up about him being a Proud Boy, they won’t think about the age discrepancy thing!” Schrader added, drawing laughter from the audience. “Then I finally said to the producer, ‘If we really want to get around the whole Proud Boy thing and get people not talking about that, let’s cast Kevin Spacey because then they’ll only talk about Kevin!’ But I couldn’t get them to go that far.”

What led Schrader away from hitting quite so many hot buttons at once was a disinterest in “getting pigeon-holed” on social media, after Focus Features, with whom Schrader collaborated on “The Card Counter,” pointed out how an errant comment by “Stillwater” star Matt Damon — who told The Times of London his daughter had recently educated him around not using gay slurs — derailed his film’s publicity tour. “You have to be really careful, in this era of social media, that you don’t feed the click-hungry wolves some raw meat they wouldn’t have had otherwise,” Schrader said.

While Schrader’s no stranger to making headlines for the provocative subject matter of his films, “Master Gardener” first came to him, as many of his past films have, as an opportunity to explore an occupation that intrigued him.

“What kind of person would be a gardener? What kind of person would be a card player? And what’s the metaphorical richness of that occupation?” Schrader said. “I’m not really interested in poker any more than I’m interested in cab driving, but I’m interested in the metaphorical richness of an occupation. ‘Taxi Driver,’ for example: at that time, people assumed that there was a cliché of a taxi driver being garrulous and funny, like your husband’s brother, and I looked at him, and I said, ‘No, this is the black heart of Dostoyevsky; this is a man in prison in a yellow steel box, floating through the sewer.’ And so you realize the richness of the metaphor when you see where else it can go. And so I started thinking about a gardener.”

In early drafts of the script, Roth had been a mobster in hiding after ratting out fellow mafiosos. Schrader was also drawn early to the idea of featuring two powerful women from different generations in the story: “If Cybill Shepherd and Jodie Foster could have coffee, what would happen?” In specifically creating Norma Haverhill, Schrader had sought an older actress who could embody the character’s imperious, often cruel personality. While speaking highly of Weaver, he revealed she wasn’t his first choice.

“Glenn Close is a lifelong friend of my wife, and she’d always say, ‘Why don’t you write something for me?’” Schrader explained. “And I said, ‘That’s not really what I write.’ But I started writing this, thinking, ‘Oh, I have a role for Glenny.’ I called her and said I finally had a role for her. I offered it to her, and she turned it down. So, she doesn’t ask me why I don’t write for her anymore.”

Throughout the talk, Schrader provided insights into his writing process. “I think the secret of screenwriting is the oral tradition of preparation,” he said, answering one audience question. “Everything you can do to keep yourself from writing is good. Keep thinking about it and talking about it until one of two things happen. Either the idea dies on you — which is a good thing because you’ve not wasted time writing it — or the idea gets so frustrated that it says, ‘Enough of this. Let’s go to work.’ And then it comes very fast because it’s been just pent up.”

Schrader singled out extensive research, however, as “a real crutch” during the writing process. “You can eventually research an idea to death, and you never write it, so you just research enough to pass,” he said. “I know enough about gardens to make people think I know more.”

Elsewhere, Schrader reflected on how real people he’d known inspired Willem Dafoe and Susan Sarandon’s characters in “Light Sleeper,” about drug traffickers in ’90s Manhattan. “It was a matter of spending a night with [drug dealers] seeing their rituals, how they did things, how the night progressed,” he said. At one point, Dafoe researched his character of John LeTour by tagging along with a dealer.

“They would go into an apartment in New York to do a drug exchange, and the customer would recognize Willem,” Schrader recalled. “But the customer would be afraid to say anything because that might blow the deal, and he wouldn’t get his drugs. Willem said, ‘You could see him really wanting to say, ‘Are you Willem Dafoe?’ But he was afraid that, the moment he said that, Willem would walk out, and the deal would be gone. So they had to choose between shaking a celebrity’s hand and getting their bindle. Any of us would make the same choice.”

On the place of humor and levity in his recent films, Schrader explained that he often uses title sequences — which he describes as “the sound the roller-coaster makes as it climbs to the ascent” — as an opportunity to teach audiences how to watch his films. “You have it to spice it up with a little comedy or, in this case of these last three films, with a phantasmagorical sequence, be it levitation, a colorful wonderland, or — in the case of “Master Gardener” — all of nature coming into bloom,” Schrader said. “This lifts the story from the prosaic into the sense there is another world running parallel to the world of these characters and that occasionally it can reach over and touch it. Occasionally, you can look over and see there is another world.”

Schrader later reflected on the role film festivals have played in supporting his work, calling himself “a product of festivals” from “Taxi Driver” onward and noting that they offer one method of separating his films from the deluge of releases on a streaming service. “A film like ‘The Card Counter’ goes to festivals, picks up some attention, and then ex-president Obama, who was in charge of the government in terms of Abu Ghraib, puts it on his top ten best list,” Schrader said, groaning. “People then see it pop up on HBO Max and can say, ‘I’ve heard about that.’ And that’s all you can ask for: that little edge on the film they haven’t heard about.”

Asked about the state of criticism by Telaroli — who quipped, “I read your Facebook posts on Twitter” — Schrader was circumspect, saying that “the problem with film criticism is the problem with audiences.” In the 1960s, he explained, along with the elevated cultural prominence of filmgoing, “there were pressing issues that people wanted addressing in the movies,” from gay liberation to female emancipation, civil rights, and militarism. “We don’t have that lobby anymore,” he said. “Movie theaters used to be shown in the lobby, and everybody came down from their rooms. Now, everybody stays in their rooms and watches movies on their devices.”

Without the shared meeting place movie theaters once constituted in popular culture, “the pressure is off for filmmakers to solve that audience problem,” Schrader said, suggesting this has made filmmaking a more niche occupation. “If you don’t have those audiences, you don’t have those movies, and then you don’t have the filmmakers, and then you don’t have the critics,” he said.

Read more from this fascinating conversation on the second page.