For over two decades, Elvis Mitchell, a film critic for LA Weekly and The New York Times, has wanted to put Blaxploitation in its proper historical place. While the results of his desire would prototypically arrive from Mitchell in the form of a book, sadly, those plans went for naught. Instead, the project Mitchell wanted to pursue languished as a mere possibility, steadily built up in smaller pieces of writing in other forms and for other singular topics, rather than as a singular actualized holistic body of work.

That is until David Fincher, and Steven Soderbergh provided the backing needed for Mitchell to get his project off the ground. Not as a book. But as a documentary that will soon be coming to Netflix.

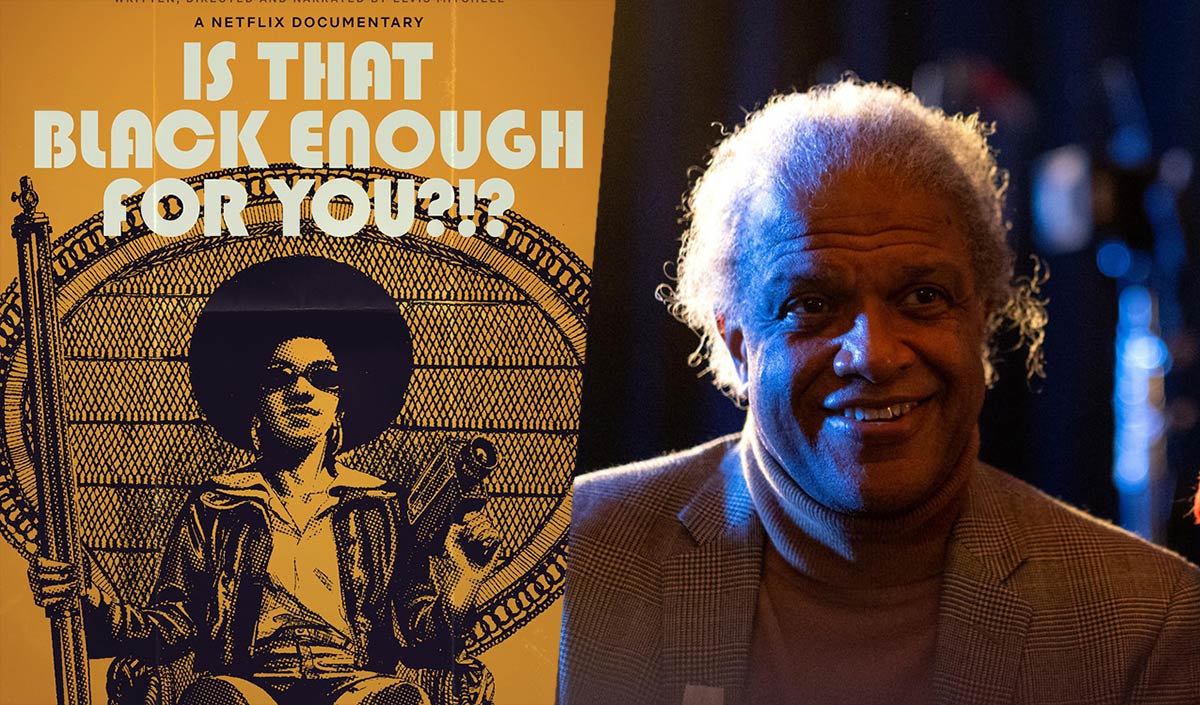

Mitchell’s directorial debut, “Is That Black Enough For You?!?” is an ambitious survey, narrated by Mitchell himself, of Black representation in cinema. It takes particular interest in the movies of the 1960s and 1970s and is a deeply personal work for the director that often weaves to and fro his own recollections of seeing these films for the first time and the timeline of importance and the scale of artistic merit they exist on.

The film combines a cadre of open talking heads: Harry Belafonte, Samuel L Jackson, Zendaya, Laurence Fishburne, Whoopi Goldberg, and more — who further put into view the imperative context of the Black men and women who played the heroes and anti-heroes of Blaxploitation classics like “Super Fly,” “Shaft,” Cotton Comes to Harlem,” and so forth, who are so often overlooked. At every turn, Mitchell makes fascinating connection after fascinating connection: How we can trace the importance of a movie soundtrack to Blaxploitation and the ways other white films cribbed from these movies’ boundary-pushing styles. While Mitchell may have needed to wait to fully realize his vision, for the audiences who are receiving this necessary documentary, which should ignite their curiosity about these films, the wait is well worth it.

I was lucky enough to speak with Mitchell on a wide range of topics, including, but not limited to, his hope for his essayist film to highlight under-noticed Black actors and movies, the origins of his film’s title, and why it’s so complicated talking about and writing about Black film. “Is That Black Enough For You?!?” is currently playing at the New York Film Festival, and it comes to Netflix for streaming on November 11. Below is my conversation with Mitchell.

When and why did you decide to make this into a film rather than, say, a book on the subject?

Because every publisher turned it down. I’m sure at some point, somebody turned it down twice. [laughs] I thought about doing it as a book, and I was at dinner; Toni Morrison, she goes: When you write the book, let me know. I’ll write the introduction. So, yeah, I did the stuff you do, and nobody wanted it as a book.

How did you get the ball rolling on the documentary?

Well, that took 23 years to happen. In so many ways, I’ve probably been thinking about doing this for most of my adult life. At Sundance in 1999, I was on the jury. And I got sort of dragooned into this filmmaker’s luncheon, and the Hughes Brothers were there, who I had not met at that point, and they were there with “American Pimp.” Before people had seen it, they thought it was gonna be like the word “pimp.” All right. This is kind of cute: Looking at the etymology of the word “pimp,” not realizing it was gonna be about, you know, pimping.

And so before that screening, in fact, screened that night and people were fleeing in droves, one of the pimps was driving around Park City with this enormous 1972 El Dorado, up and down main street like a one-man parade procession in this car. And so anyways, I ran into them, and we were just talking, and I asked them about using “Walk on By” by Isaac Hayes. That feels like a piece of movie music. And Albert said: Well, you know, that’s because — and we said this in unison — he stole it from “Once Upon a Time in the West.” That’s when I thought: Okay, I’m not the only person who thinks like this. A lot of people look at that period of movies and the conversations that these movies are having about popular culture and the social climate of that time.

The unfortunate thing about taking as long as it did [to make this] was that so many people who agreed to talk to me passed away. I had Isaac Hayes, who was gonna do it. In fact, the day we shot with Harry Belafonte was the day that Diahann Carroll died. And so we were a little concerned because I was lucky enough that for that shoot with Harry, my cinematographer— for the first thing I ever directed— was Steven Soderberg. We were in the van thinking Harry might cancel, and I said: Well, let’s just go and see what happens. Let’s not scrub this thing just yet. We get in and Harry just says: Well, you heard about Diane today? It’s awful. Let’s go to work.

It may have taken a long time for this to happen, but sitting down with him, finally, I’ve been around him a few times before, he has the same kind of clarity and force and moral outrage in his nineties as he did when he was in his thirties and twenties. He’s got this incredible recall and still has these same feelings. A lot of these slights he felt had the same sort of impact on him 60 years later as they did when he was experiencing them. So that made me know that I was on the right track with this.

When Belafonte says in the documentary: “Fuck you. I’m going to Paris” – I want to get that tattooed one day. Did you only have one day with Belafonte?

It was an hour and a half. And it was so great because he’s just brimming with energy, even as he’s just sitting there. You’re thinking: He could have played Don Corleone. He could have had any number of things. You just think about what he could have done; because just to radiate that kind of star presence in his nineties without moving. I was awestruck by it. That’s not a word that people hear me use in terms of talking about celebrities and being around famous people, but he just had that kind of charisma.

He was always, to me, the spine of this. Whenever I would talk to people about it, I would say it’s Harry Belafonte who walked away from the movie business rather than do things he thought were insulting to him and his people. I can’t think of another case of somebody doing something like that. It was a wonderful thing to have him there and to be able to talk to him and capture him on camera. But it also sent this chill in me because, finally, to me, this movie is about wasted opportunity. Just how so much Black talent wasn’t given its due.

The story of Rupert Crosse, who, for me, I can’t hear him speak and not hear the same kind of vocal cadence as Jack Nicholson. You can hear him, and you can hear the impact that he had on Jack Nicholson as an actor in the same way he pauses, and even the laugh and that kind of mirthless chuckle that sizes you up. Diana Sands also should have been a movie star and wasn’t. Ivan Dixon too. You see “Nothing But a Man,” where it’s Ivan Dixon and Abbey Lincoln, and you go: Oh my God. If this is not the definition of racism that you refuse to see the star power between these two people.

I just saw “A Man Called Adam” at TCMFF and wondered: How wasn’t everyone admitting that Sammy Davis Jr was the best actor in the Rat Pack?

The first half of that movie is Sammy Davis Jr and Cicely Tyson. Where are the essays about Cicely Tyson and Sammy Davis Jr. being on screen together? And him holding his own with her as an actor, but not upstaging her. Because that’s something that you saw Rat Pack actors do as a kind of prankishness, where they had all this sort of star power, but they would upstage somebody just because they were jerks. But Sammy Davis Jr has a kind of generosity as an actor.

Here’s the thing, whenever there’s one of these sorts of big tribute reels or some book about the greatest moments of movie history, there are never any moments from Black movies. Ever. And so I just tried to spotlight some of these moments. I mean, for me, in that chase sequence in “Super Fly,” he’s running in the streets of Harlem wearing a suede suit, and he vaults a five-foot fence in heels and then jumps up onto the fire escape and pulls himself up. That sequence is not in any movie about the greatest action sequences of all time. It’s a complete and utter astonishment to me. And that’s just one.

Just about all of the chosen talking heads are linked to the movies being discussed. Except for Zendaya. What was the thought process behind including her?

It was just a question of who was gonna say “yes.” It’s just that simple. Unfortunately, we started shooting during Covid. So people, and I’m not gonna mention their names ’cause I don’t do this, but people who were older didn’t want to take the chance of being around a film crew. I mean, we had to quarantine for five days before we could go up and shoot. So, was everybody in masks. And it really was an anxiety-producing situation there. So there were people who just couldn’t do it or wouldn’t do it because they didn’t wanna risk their lives to be in some goofy documentary, and who could blame them?

Unfortunately, by the time we started to shoot, Melvin Van Peebles was suffering from Alzheimer’s. So he wasn’t available. But I knew Mario [Van Peebles] could do it. I always wanted to interview Roscoe Orman, just because I think he’s an incredible actor. And I think what he does in that “Willie Dynamite” is kind of astonishing. William Greaves, unfortunately, was somebody who passed away by the time we did this. I knew Louise Greaves could talk about him. Sheila Frazier, just because she’s got a sense of humor about being in “Super Fly” and being a part of that period. And again, Jim Signorelli, just because he had done so many different kinds of shooting. He was a kid when he shot “Super Fly,” but he could speak really fascinatingly and eloquently about trying to surmount all those obstacles: shooting 16mm, operating the camera himself as the car’s coming down the street, and that kind of problem-solving that they ended up doing to make that movie happen.

But you were asking about Zendaya. I thought it was important to get somebody, a younger person who had some sense of film history, who knew that she was a part of this continuum and she’s not the only one. But I just thought it’d be great to get somebody who’s a movie star, who radiates the same kind of presence as Harry Belafonte or Roscoe Orman or Sheila Frazier does.

Read more of this conversation on the second page.