There is nothing in Robert Kenner‘s "Merchants of Doubt," his follow-up documentary to 2008’s fascinating expose of corporate malfeasance in the food sector "Food Inc," that we disagree with, or even want to weakly rebut. Nothing. The fluidly argued points flow with flawless logic one into the other, and the manner in which he traces the strategies used currently by vested interests in defence of their bottom lines, straight back to the playbook set out by Big Tobacco in the 1950s is irrefutable and wholly convincing, especially when presented in so enjoyably arch and ironic a manner. We vehemently agreed, laughed along at the more incredible and egregious fallacies highlighted, and could feel every single other member of the audience at our Goteborg International Film Festival screening doing the same. And that’s a problem.

There is nothing in Robert Kenner‘s "Merchants of Doubt," his follow-up documentary to 2008’s fascinating expose of corporate malfeasance in the food sector "Food Inc," that we disagree with, or even want to weakly rebut. Nothing. The fluidly argued points flow with flawless logic one into the other, and the manner in which he traces the strategies used currently by vested interests in defence of their bottom lines, straight back to the playbook set out by Big Tobacco in the 1950s is irrefutable and wholly convincing, especially when presented in so enjoyably arch and ironic a manner. We vehemently agreed, laughed along at the more incredible and egregious fallacies highlighted, and could feel every single other member of the audience at our Goteborg International Film Festival screening doing the same. And that’s a problem.

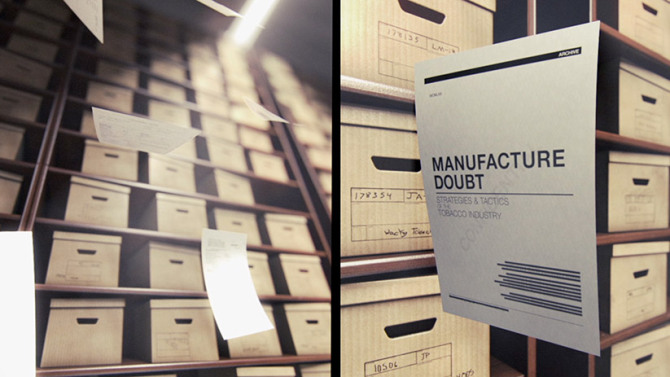

"Merchants of Doubt," inspired by the Naomi Oreskes and Eric M Conway non-fiction book of the same name, (Oreskes appears in the film as one of the many interviewees, from both sides of the aisle) takes aim at the strategy of spin, obfuscation, deflection and distraction that is employed by powerful corporate interests such as the oil lobby, cigarette manufacturers and the flame retardants industry. But the problem is tone: this is not a film that is trying sincerely to convince anyone of anything that they don’t already believe. And from its pointlessly showy computer animations (not really sure why they had to CG a transition which involves CG paper being taken out of a CG filing cabinet and copied on a CG photocopier) to its flashy framing device in which magician Jamy Ian Swiss draws frequent parallels between the mechanisms behind conjuring tricks and those used for mass-manipulation, it feels like a package that has itself been smoothed out and glossed up using very similar techniques to those it critiques — as though it has itself been spun.

No real attempt is made to understand why the stories the corporations are spinning are so seductive to masses of people, nor to get into any other mindset, instead the film is content to suggest that they are the misguided, duped other guys, the out-of-town bumpkin marks in this high-stakes game of three-card monte and we, the enlightened, can only tut and sigh and scorn their delusions. Which is fine too if that’s the remit, except that then Kenner demonstrates directly just how far this approach falls short, by devoting the lion’s share of the (occasionally draggy) run time to climate change.

When talking about Big Tobacco and the birth of spin ("Doubt is our product" reads the brilliantly chilling mantra developed by the PR company hired to counter reports that cigarettes were bad for you), or telling the fascinating tale of potentially harmful chemical flame retardants in furniture, and how they became law due to the cigarette companies’ strategy of shifting blame for house fires away from their products and onto the stuff that burned instead, "Merchants of Doubt" is highly enjoyable. But these are stories of victory, albeit a long time coming (50 years later the cigarette companies were legally mandated to admit they lied to the America public; flame retardants are no longer the letter of the law).

Climate change is very far from a story about the eventual triumph of informed and rational thinking over corporate interests — it’s an intractable ongoing issue on which the clock ticks ever louder. So while it might be fun to cheer small liberal victories — times an actually informed pundit or scientist has gotten the upper hand in a televised "debate"; instances of evil old white men being unmistakably caught in a lie of their own telling; the unanswerable facts of pundits’ lack of qualifications and money trails that lead back to the same corporations like a trail of bloody footprints — they all feel like pyrrhic victories when stacked up against the battle not yet won. And then suddenly the whole film feels like an empty exercise in winning the hollow last laugh — the ship is sinking, and being so much righter than the other guys is cold comfort when the water’s about close over all our heads.

Kenner rightly points out that addressing the issue of climate change requires a major shift in public opinion, which is actively being hampered by the same corporate strategies that have been used to mould public debate for decades. But the people whose minds need to be changed, and whose eyes need most to be opened to the insidious manipulation to which they have been victim, like the audience for the Red State radio show that ex-congressman Bob Ingliss guests on, only to be roundly derided by its grossly misinformed host for attempting to talk reasonably about climate change, are going to stay a million miles away from this documentary. And the few who wander in by mistake will find themselves on the outside of its conspiratorial "you know and I know" approach and may therefore very well find all their preconceptions about liberals as a bunch of smug know-it-alls well-founded, ducking out with their own views possibly more entrenched than ever.

Kenner rightly points out that addressing the issue of climate change requires a major shift in public opinion, which is actively being hampered by the same corporate strategies that have been used to mould public debate for decades. But the people whose minds need to be changed, and whose eyes need most to be opened to the insidious manipulation to which they have been victim, like the audience for the Red State radio show that ex-congressman Bob Ingliss guests on, only to be roundly derided by its grossly misinformed host for attempting to talk reasonably about climate change, are going to stay a million miles away from this documentary. And the few who wander in by mistake will find themselves on the outside of its conspiratorial "you know and I know" approach and may therefore very well find all their preconceptions about liberals as a bunch of smug know-it-alls well-founded, ducking out with their own views possibly more entrenched than ever.

"Merchants of Doubt" teaches us with energy and wit that spin is so much about telling people what they want to hear — that they don’t have to change, that they were right all along, that if there are problems they belong to other people. But the film’s own spin toward a liberal audience means it chokes into ineffectuality when it tries to take a less ironic and more active stance on society’s biggest current white whale, because the persuasive sermon it preaches, it preaches exclusively to the choir. [B-]

I felt the same about the wildly overrated doc The Cove about five years ago.