To those who have accused the contemporary Sundance Film Festival of tending to favor a particular kind of narrative or documentary feature, “Seventeen” will serve as evidence that at one time, the jurors in Park City stood behind dangerous or risky filmmaking, and certainly the documentary from Joel DeMott and Jeff Kreines comes backed with a helluva story.

To those who have accused the contemporary Sundance Film Festival of tending to favor a particular kind of narrative or documentary feature, “Seventeen” will serve as evidence that at one time, the jurors in Park City stood behind dangerous or risky filmmaking, and certainly the documentary from Joel DeMott and Jeff Kreines comes backed with a helluva story.

In 1982, PBS was gearing up to air “Middletown,” a miniseries that would take viewers to Muncie, Indiana where they would get an intimate, unfiltered view of middle America. But there was just one problem. The sixth part by DeMott and Kreines, “Seventeen,” ran afoul of Xerox. As the corporate sponsor of “Middletown,” they were offended by the foul language and, perhaps, controversial content found within the episode, and so it never made it to broadcast. However, it did make it to Sundance in 1985, where it earned the Grand Jury Prize in the documentary category. However, the question is, thirty years later, does “Seventeen” stand on its own, and did it deserve the notoriety it had at the time? The answer is a bit of a mixed one.

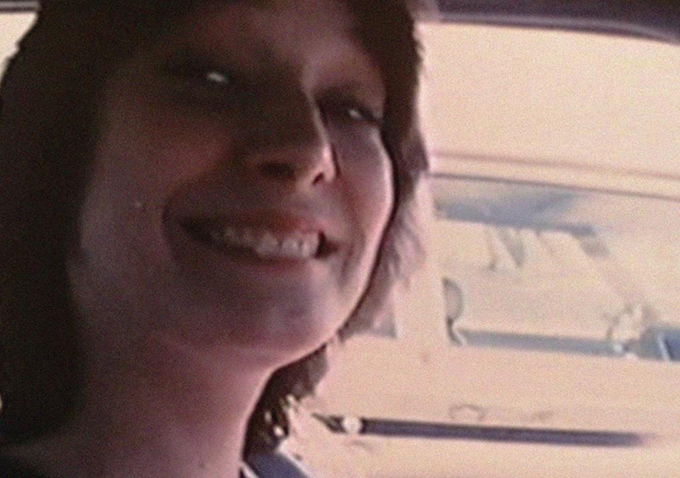

Certainly, the filmmakers couldn’t have asked for a better subject than Lynn, the high school senior who takes central focus for the two hour doc. She smokes, cusses, and swings wildly between happiness, anger and despair like any teenager driven by nicotine, hormones, and FM radio rock. And she brings some interesting baggage to the table, namely a brewing interracial relationship with John that she’s wary of making known to her parents, particularly her mother, whose antiquated view on race relations is couched in a veneer of suburban politeness. Lynn is also just a big personality, whose charisma often carries “Seventeen,” which otherwise doesn’t move in any specific direction, preferring to hang on Lynn, and follow her wherever she goes next.

It is particularly when it involves her attempt to build a solid, steady relationship with John, that it’s interesting to see how the perception of race unfolds in the early ‘80s. As Lynn posits during one eye-opening argument with John, if she chooses to date a black man, it’s a strike against her character, while he won’t face any social repercussions for doing the same. Things take an even more surprising turn when a cross is found burning on Lynn’s lawn (disappointingly not captured on camera)—however it’s not fear that follows, but outrage by Lynn, and an almost casual acceptance that these kinds of things just happen.

It’s certainly the kind of material that can leave audiences shocked; one does wonder about the choice of Lynn being representative of youth in Muncie. She certainly makes for good television, and the razor sharp focus by the filmmakers on her life is certainly rare, but one wishes for context. Perhaps watched within parameters of the rest of the “Middletown” series “Seventeen” is a bit more balanced, but released on its own (it was previously available a boxset of the series) and celebrated in some corners as a cherished documentary artefact, one can’t help but ask if this is really what it’s like for Muncie teenagers. What is the racial and economic make up of the town and how does it affect prejudice? As far as “Seventeen” is concerned, it could be argued that a more accurate title might simply be “Lynn.” This is undoubtedly her experience but to try and argue it as a representation of a broader population her own age raises questions, but why John, the major equation of Lynn’s storyline, doesn’t get his own camera time is a mystery. A lack of input from African-Americans was a criticism of the original “Middletown” studies from the 1920s, which this documentary is inspired by, but the filmmakers don’t correct that error to any significant degree.

Oddly enough, it’s the less sensational segments that ring far more true. The rowdy home economics classroom of the indefatigably patient Ms. Hartley who tries to teach is what could easily be called a hostile environment (she is the target of more than few epithets) is a fascinating backdrop to watch Lynn and her classmates interact. An end-of-year message from a sociology teacher to his class that life is half hard work and half good luck is surprisingly sobering, and a brief snapshot of a championship basketball game, and the aftermath, is also a nice window into the community the filmmakers explore (though you’ll have to track down the second part of the series "The Big Game" for more).

Three decades later, “Seventeen” is certainly a fascinating document and it’s undeniably watchable. Whatever its credentials as a documentary in terms of an accurate snapshot of life in a Muncie high school creates a fascinating talking point after any screening. Its decidedly raw, unvarnished, unapologetic approach is certainly leagues away from the highly scripted, carefully polished genre entries that are standard now. “Seventeen” leaves you with much to mull over, not just in its form, but also its content. “Do you know where your children are?” was a popular public service refrain for years, but the question “Seventeen” asks isn’t whether someone is watching our children or not. The filmmakers have turned their camera on them, and the bigger query to be answered is, “What do we do now?” [B-]

"Seventeen" his DVD and VOD on August 18th.

"…at one time, the jurors in Park City stood behind dangerous or risky filmmaking."

The jurors that year were D.A. Pennebaker, Barbara Kopple, and Fred Wiseman. Not exactly chopped liver.

This review seems to be fixated — pretty foolishly IMHO — on treating Seventeen more as a controversy than as a film. No one has given any thought to Middletown or Peter Davis for over thirty years, for obvious reasons.

I found these online — they will give you better information about what really happened to the film and the filmmakers.

Unfortunately, Indiewire won\’t let me post any links. Go to the Wikipedia page for the film and you will find the links, which are fascinating.

This is not the filmmaker\’s version of Seventeen — it is a hideous looking version of a beautiful movie. (I saw it at BAM last week.) Don\’t buy the DVD. Any version that does not have handwritten titles is a terrible (not to mention censored) desecration of a great film. Whoever put this version out should be ashamed of themselves.