4. “Porco Rosso” (1992)

4. “Porco Rosso” (1992)

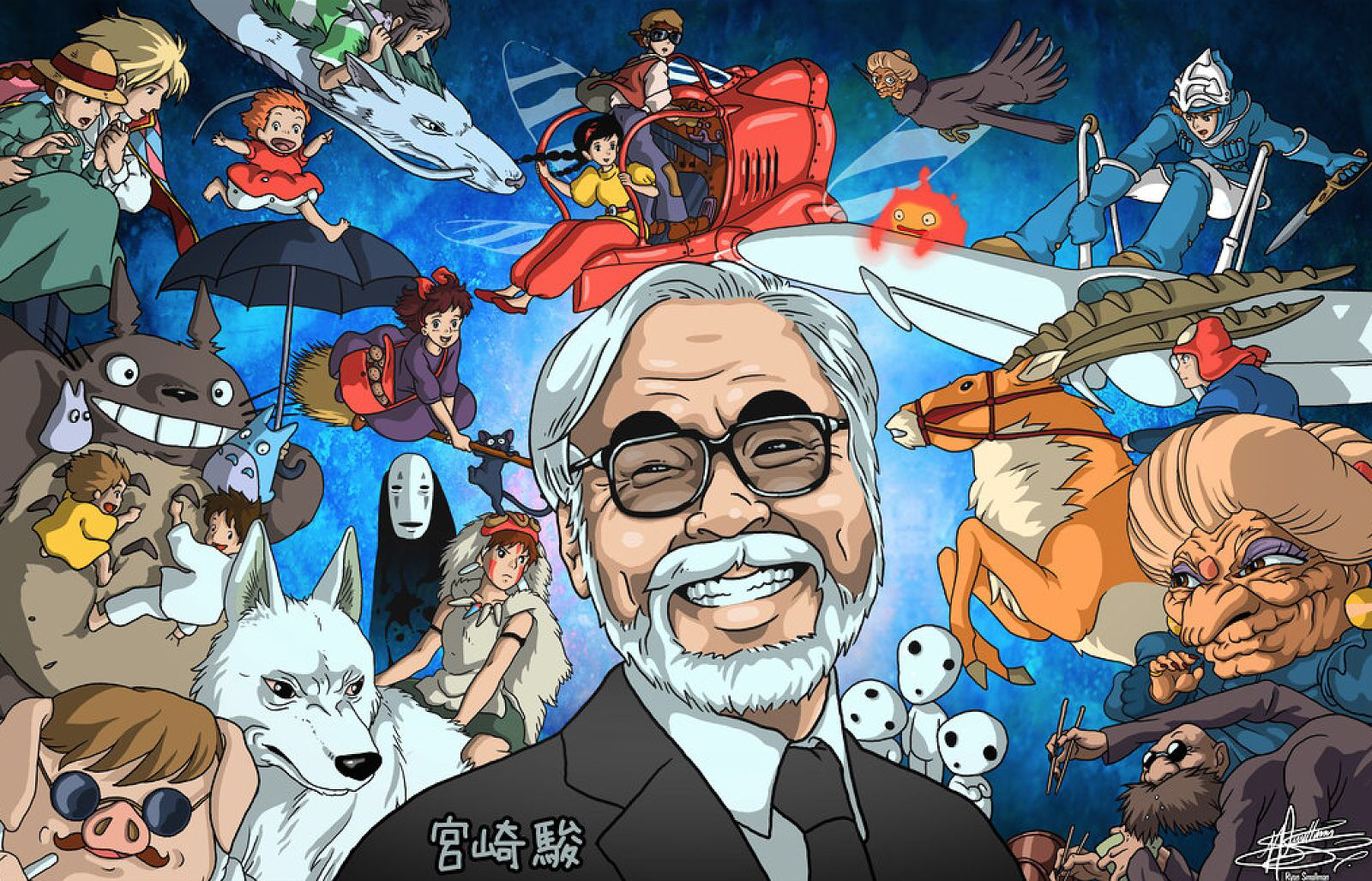

Frequently cited as one of the director’s weirdest films, mainly because it’s hardly weird at all, “Porco Rosso” could almost be a straight-up Tintin-style historical fiction of derring-do, were it not for the fact that its hero is an aviation ace who, under an only-vaguely-explained curse, is an anthropomorphized pig. In fact, the whole being-a-pig element is one of the least striking things about Porco/Marco, as the film works wonderfully well as a portrait of a kind of Bogart or Mitchum-esque cynical hero, who likes to believe he’s only out for himself, but who comes slowly into his heroism via a series of adventures, an exposure to the innocence of a talented young female engineer, and, of course, the steadfast love of a good woman. Cursed to live as a pig as punishment, he believes, for surviving a WWI dogfight in which all his comrades died (this sequence is rendered as a flashback and is one of the loveliest, saddest parts of the film), Marco is now called Porco and makes his living as a bounty hunter based on an island in the Adriatic. Getting his plane fixed in Milan, where he is wanted for desertion (refusing to fight for the Fascists), he eventually flees with Fio, a young plucky female engineer, only to become entangled in an old rivalry with Curtis, a brash American flyer. The film is unusual in the Miyazaki catalogue for the specificity of its real historical time period (interwar) and geography (right down to the markings on the aircraft, as well as the references to Fascist Italy), but shows more than a little love for one of his recurring themes: the romance and pioneering spirit of aviation. Little wonder this film originally began life as a short in-flight movie for Japan Airlines (we wonder if that’s where the affectionate but mischievous portrayal of the American started too—the Lindbergh-ian Curtis is a square-jawed, foolhardy daredevil who falls in love with every woman he meets and eventually returns home to become, what else, a movie star). For once forgoing allegory for straight-up commentary, “Porco Rosso” is one the Japanese master’s most straightforward stories, and just as compelling and imaginative for it. It may be set, with admirable authenticity, against the backdrop of an identifiable time and place, but the story still aspires skyward, detailing nothing less than the gradual reclamation of a man’s soul (okay, man-pig’s soul) from where he’d packed it away in disgust at the warring world, and at himself.

3. “Spirited Away” (2001)

A few of Miyazaki’s movies can be read as riffs on classic fairy tales, and “Spirited Away” is one that takes the basic premise of “Alice in Wonderland” and mutates it, wonderfully, into something altogether unique and at times unsettling, accurately embodying the jaunty uncanniness of Lewis Carroll‘s trip in a way that many straight-up adaptations have failed. “Spirited Away” follows Chihiro and her parents, who are turned into pigs while gluttonously chowing down at a restaurant stall, and wander into an alternate, upside-down, inside-out universe. Like any of these stories of childhood wish fulfillment, Chihiro first enjoys the magical realm and its freedoms, with her parents confined to a pigpen, and new playmate to show her the ropes. But she soon has to grow up and battle the malicious spirits that inhabit this universe (personified by the eerie No-Face character), all while learning the rules of a world where forgetting your name is surrendering yourself to another’s control, where the spirits of polluted rivers pay you in vomit-inducing dumplings to feed to your enemies, and where everything is something else in disguise. Hauntingly beautiful and really very odd, “Spirited Away” served as something of a second breakthrough for the director, winning the Oscar for Best Animated Feature. It’s a testament to Miyazaki’s considerable prowess as a storyteller that the “coming of age” element of the movie’s narrative never gets overshadowed or drowned out by the story’s magical elements and mythical creatures; all children want their freedom and think that their parents are pigs, but it’s when these ideas become literal that the child’s true character is tested. “Spirited Away” is at once one of the most readily likable, and one of the most foreign of all of Miyazaki’s film—a lovingly embroidered fable that will carry you off to a place of pure imagination, but is not afraid to dwell at times in its darker recesses, which hide some pretty eerie elements too.

2. “My Neighbor Totoro” (1988)

This might be Miyazaki’s most iconic work to date, partially because the character of Totoro, a giant, magical rabbit/cat creature, has become the de facto mascot for Studio Ghibli, appearing on its logo and spawning countless merchandising opportunities. But this is also the film that established Miyazaki as the animation world’s version of Terrence Malick—more concerned with contemplative, spiritual moments of extreme quiet than with how much cluttered nonsense can fill the screen. “My Neighbor Totoro” is set in post-war Japan, in a rural village where a man and his two daughters move into a small house so they can be closer to their ailing mother. It’s here that the girls discover the magic of the natural world that is all around them; tiny dust balls in the empty house are actually creatures, and the woods are filled with pointy-eared spirits, the most cuddly of which one of the girls dubs Totoro. There are a number of moments in ‘Totoro’ where Miyazaki just allows the wind to rustle the grass and the sunlight to drape over the girls, emphasizing the magic of everyday life and the importance of slowing down long enough to recognize it. The design work of the film, from Totoro and the other magical creatures to the amazing Catbus, is second to none, simple and daintily surreal. Watching “My Neighbor Totoro” you’re filled with awe and wonder; in the Miyazaki universe, the magical world and the real world exist side by side, it just takes an open heart and wide-eyes to notice. Real-world medical issues, for example, are placed alongside the dramas of that mischievous spirit world without judgment and without weighing one as more important than the other, which is more than surprising—it’s miraculous. As we mentioned, John Lasseter, the hula-shirt-wearing Pixar bigwig and director of the original “Toy Story,” is a huge fan of Miyazaki and ‘Totoro’ (he has the face and front paws of the catbus sticking through the walls of his office), to the point that in “Toy Story 3,” in a gesture that is positively neighborly, one of Bonnie’s toys is a plush Totoro. This, however, is one of the cases where going back to the original, that has inspired so much since, will not disappoint.

1. “Princess Mononoke” (1997)

It’s hard to pick a number one Miyazaki film without it coming down to the wire of personal preference and memory. But going with our heart, it beats out a steady rhythm we can’t ignore—Mo-no-no-ke. Miyazaki’s first major crossover hit (though not without its hiccups: Harvey Weinstein was only dissuaded from cutting it down for U.S. release when he allegedly received a Katana—samurai sword—in the mail from the film’s producer with a note that read pithily “no cuts”), the film’s U.S. release was actually somewhat bungled, considering its record-breaking Japanese run and it was only after international response was strong and the DVD sales immense, that ‘Mononoke’ really established Miyazaki’s and Studio Ghibli’s international box office credentials. But in what style! The film immerses you in a universe at once relatable and beyond imagination, in which otherworldly creatures and visuals are used to comment eloquently on very real-world issues, in a manner that is clearly delivering a message, but is never less than thrilling. Embodying a beautifully unpreachy environmentalist core, and working in Miyazaki’s trademark “futility of war” theme, “Princess Mononoke” follows a young warrior, Ashitaka, who is banished from his village after an act of valor results in him being cursed, as he voyages to a far-away land of forest spirits, Wolf and Boar-Gods, and men and women, both venal and noble, often at the same time. Here he meets and falls for the titular princess, the human daughter of the Wolf-God (she identifies Wolf), but is caught between the sides when the human population of Iron Town, whom he has befriended, led by haughty Lady Eboshi, wage war on the forest. What’s so astonishing, for what is ostensibly a children’s film, is the complexity of the characterization and Miyazaki’s absolute confidence in presenting an ambivalent, often contradictory picture of right and wrong. Where Eboshi could easily be a villain, here she is also a crusader (of distinctly feminist bent), gathering a doggedly loyal following of ex-prostitutes and lepers and other “unwanteds” to create an iron-mining stronghold out of nothing. Of course, at the same time, she is denuding the forests nearby and robbing the old Gods of their habitat but she is neither one thing nor the other, just as Mononoke is neither wolf nor human, and Ashitaka is neither the straightforward hero, nor the demon that he has been cursed to carry in a wound on his arm. Painting with the fullest palette of emotions, from love and empathy and kindness to hatred and rage and fear, “Princess Mononoke” is perhaps the finest expression of Miyazaki’s visual inventiveness (the story goes he personally redrew about 80,000 of the 144,000 cels in the film) uniting seamlessly with his thematic concerns and his unparalleled storytelling. Immersive, transportative and breathtakingly beautiful, it is everything that is Miyazaki and it reminds us how, at his very best, Miyazaki can be everything.

Honorable Mention: For the completists among you, there’s more to be found, as Miyazaki was at least a producer on almost everything that Studio Ghibli ever made, with the exception of the devastating masterpiece “Grave Of The Fireflies,” and a few of that film’s director Isao Takahata‘s other pictures. Miyazaki produced “Only Yesterday,” “Pom Poko,” “Whisper Of The Heart,” and “The Cat Returns,” all of which are worth checking out to some degree or another. More recently he also co-wrote “The Secret World Of Arrietty” and “From Up On Poppy Hill,” the latter of which is his first collaboration with his son Goro Miyazaki (who also directed the Ghibli-produced “Tales From Earthsea“).

There’s also some short-form work to chase, including on TV series “Lupin III,” “Future Boy Conan,” and “Sherlock Hound.” Miyazaki also helmed a music video for Japanese band Chage & Aska‘s song “On Your Mark,” and a brace of shorts that are mostly only to be found in the Ghibli Museum in Tokyo—”Whale Hunt,” “Koro’s Big Day Out,” “Mei and the Kittenbus,” “Monmon The Water Spider,” “House-Hunting,” “The Day I Harvested A Planet” and “Mr. Dough and the Egg Princess” are the ones to look out for if you’re ever in the neighborhood.

And to close off, two videos: one is the gorgeous tribute to Miyazaki that recently aired on “The Simpsons,” and is the best thing the show’s done in at least a decade, the other a chance to see the director make ramen for his Ghibli team, taken from the DVD for “Spirited Away.” — Drew Taylor, Jessica Kiang, Oliver Lyttelton