40. “The Assassin” (2015)

No film since “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” has celebrated the wuxia genre as masterfully as Hou Hsiao-hsien’s “The Assassin.” The Taiwanese filmmaker’s first effort since 2008’s “The Flight of the Red Balloon” is a languid, melancholic meditation on personal sacrifice and integrity. Shu Qi — in a stoic, heartrending turn — stars as Yinniang, a peerless assassin tasked with killing her childhood sweetheart (Chang Chen) in order to upset the balance of power between the imperial capital and the remote province of Weibo. On first pass, the intricacies of eighth-century Chinese politics are impenetrable. But even if the details of the plot become more legible with each successive viewing, it hardly matters. To watch “The Assassin” is to enter into a transcendent cinematic meditation: the rustling of leaves, a gentle breeze passing through sheer curtains, flickering candles flames, cinematographer Mark Lee Ping-Bing’s hypnotic slow pans, and long takes. The flash of Yinniang’s dagger isn’t meant to draw blood; rather its mere lethal presence encourages a détente. Hou doesn’t glamorize violence inasmuch as he acknowledges its inevitability and honors the dignity in walking away from a fight. – BW

39. “The Handmaiden” (2016)

A deliriously pleasurable conman and caper movie that packs in an erotic fantasy storyline too, Chan-Wook Park’s ravishing movie, lush in its overall dressings, centers on a shrewd woman secretly involved in a plot to defraud a Japanese heiress by infiltrating her life as a handmaiden. About the sensual charge of stimulatory power dynamics as it is about the perils of romantic obsession, “The Handmaiden,” may seem, at first blush, like a traditional Chan-Wook Park movie. But all it takes is some graphic lesbian lovemaking, a freaky kabuki intermission, and the presence of a particularly terrifying squid-like creature to dispel us of this particular notion. A lesbian love affair, jealousy, and twists and turns threaten to undo every conniving, slippery plot. Exquisitely rendered, perhaps the most gorgeous-to-look-at film of 2016, its stylish cinematography, costuming and every production design element is impeccably sewn. Graceful and razor sharp when necessary, “The Handmaiden,” is arguably the masterpiece Chan-Wook Park has been threatening to make his entire career. – RP

38. “Two Days, One Night” (2014)

Dramatically tense and wrenchingly captivating in a realist manner only made possible by the Dardenne Brothers (“Rosetta,” “L’Enfant”) “Two Days, One Night” unfolds like a slow cinema version of “12 Angry Men,” about workplace rights, as well as human empathy. A group of factory laborers are given the choice of voting to either fire a fellow worker, Sandra (Marion Cotillard) or keep their hard-earned bonuses. Economic stability overshadowing ethics and emotions, and her co-workers chose the former, forcing Sandra to individually plead her case to 16 different employees over the weekend, desperate to keep her source of income intact. The narrative conceit sounds like it could get cold and repetitive, but Sandra’s attempt to fight for control in a world ruled by capital is intensely watchable from start to finish, ending with one of the most anxious sequences the brothers have shot with their trademark, jolting aesthetic to date. Cotillard is frighteningly good, especially in her grueling depiction of despair and the way the undertow of depression can engulf and drown the soul—perhaps her most heartbreaking performance yet. Like many of their finest films, it’s a work defined by philosophy but grounded in the thrust of working-class citizens’ everyday struggles, ones that parallel the world in which we all live in a variety of complex manners. – AB

37. “Certified Copy” (2010)

What distinguishes our individual desire towards a better understanding of the soul? The late, great Abbas Kiarostami treated the art house world to an unexpected late-career, love poem with “Certified Copy,” a European language film that is now counted among the Iranian artist’s essential works. One of the most confounding movies of his career “Certified Copy,” questions what distinguishes an original work of art from just a really good forgery, if there even is such a difference. Being a Kiarostami movie, the metatextual filmmaker takes his core idea and turns it back on the very subjects that present it. Beginning as a discourse on the meaning of art, before the narrative flips itself upside down, “Certified Copy” is a self-reflexive examination of copy-cat human dynamics. Starring Juliette Binoche in one of the greatest roles of her career (which is saying something) opposite William Shimmell (an opera singer with academic cadence and remarkable charisma, in his first film role), “Certified Copy,” is the kind of film that can be viewed endlessly and one will still find new ideas inside the frames within its frames. The project felt like the start of a new era in a singular artist’s career; it’s simply a masterwork so profoundly mature that it makes one wonder how many creative gems the film world was robbed of when Kiarostami passed away. – AB

36. “Holy Motors” (2012)

An utterly bananas work of outsider art, Leos Carax’s “Holy Motors” has few contemporaries – even the filmmaker’s own mad and mischievous “Mauvais Sang” and “Pola X.” An immaculate feature-length hallucination, it unravels in delicate and sometimes alarming layers, only to put itself back together again in cock-eyed new dimensions. Denis Lavant, one of the most chameleonic performers to grace a movie screen, gives perhaps his definitive performance here – a cross between Buster Keaton and the Looney Tunes character of your choosing. Any movie whose penultimate scene depicts a conversation between a garage full of identical limousines is certainly not aiming for accessibility. But there is aberrant integrity in Carax opting to make his movie in a way that, presumably, closely resembles the strange visions that tumble around in his wild, idiosyncratic mind. – NL

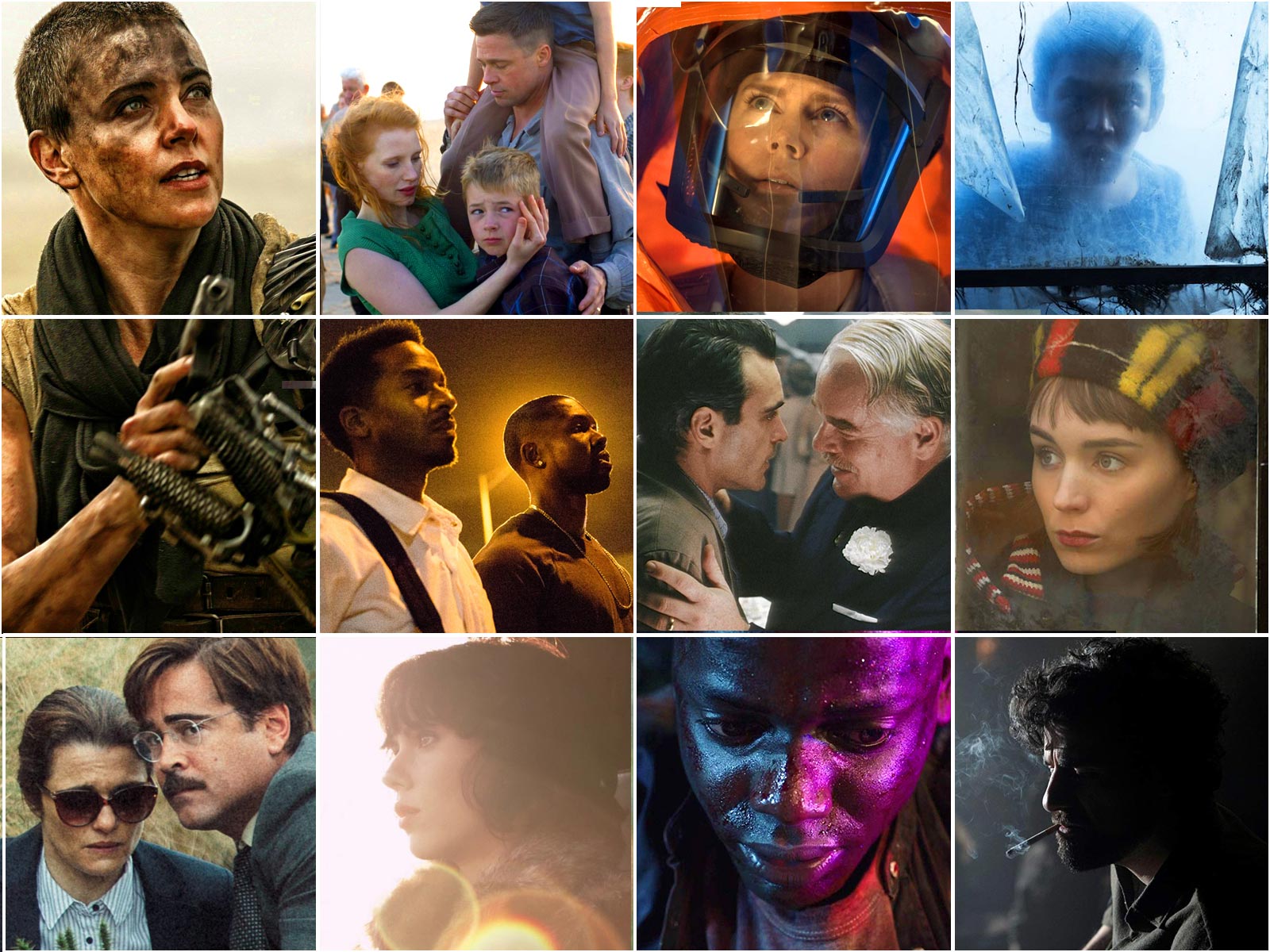

35. “If Beale Street Could Talk” (2018)

Producing a worthy follow-up to a film like “Moonlight” must seem like an impossible task. “Moonlight,” and its striking sense of empathy and dreamy balm, left moviegoers shook: how could any director helm an encore for such a culturally relevant and influential work? Luckily, the thoughtful writer/director Barry Jenkins is simply one of the best in the business, and “If Beale Street Could Talk”—his transportive and beautiful adaptation of James Baldwin’s seminal novel—is as worthy a curtain call as any of us could have asked for. The story of star-crossed lovers Fonny (Stephan James) and Tish (KiKi Layne) in 1970s Harlem, ‘Beale Street’ is a stylistic leap forward for Jenkins from the more pared-down, intimate humanism of “Moonlight,” while nevertheless retaining the director’s focus on marginalized characters, the pains of personal liberation, and the thrill of forbidden romance. The film is also an irrefutable technical feat, showcasing gorgeous cinematography from James Laxton, a breathtaking score from the great Nicholas Britell that evokes courage in the face of uncertainty, and warm, marvelous supporting turns from the likes of Colman Domingo, “Atlanta’s” Brian Tyree Henry. Plus, you know, national treasure Regina King. – NL

34. “Parasite” (2019)

It might sound hyperbolic to say that some works of art simply feel like the piece the creator was put on this earth to make, but that’s exactly the case with Bong Joon-ho’s black comedy of manners, chaos chamber piece, and biting social/class critique, “Parasite.” Following a family of 4 — your everyday Korean domestic unit (The Kims) — who happen to be con artists that fashion a series of plans to insinuate themselves into the lives of an upper-class household (The Parks) by posing as doppelgangers of their help. The situation quickly escalates in insanity, and the diabolical methods concocted by the Kims is really only where the plot starts getting crazy; Bong’s hot sauce hasn’t truly hit the fan yet. Quite possibly the best and most original screenplay written this year, “Parasite” operates on an unpredictable number of levels, constantly increasing in both tension and creativity; and the escalation, never stops, continuously shaking the very foundation of any semblance of expectation. Composed primarily with geometric shapes and similar camera motifs, Bong’s filmmaking is so coded and confident it’s almost as if the director was painting with a brushstroke blindly; his movie is bursting at the seams with symbology, and yet the text is seamlessly woven into the uproarious fabric of the comedy. Just when you think you have his masterpiece pinned down, Bong hits you over the head with an image or idea that you know will be rattling around your brain for the rest of your life. Believe the Bong d’Or hype. – AB

33. “American Honey” (2016)

The 2010s were nothing if not a cacophonous bombardment of entertainment in many shapes and sizes, all vying for the attention of a new generation of young people who began the decade full of hope and ended it with the devastating awareness that they might be the most economically fucked generation ever. You might not peg 55-year-old, English-born director Andrea Arnold as the filmmaker to shine a light on such a tumultuous, uncertain time in American culture, but that’s exactly what she did in 2016 with her sprawling, free-wheeling epic “American Honey.” Arnold set her sights on a land foreign to her and a generation far removed from her own, capturing the zeitgeist of two generations intersecting between youthful abandon and the looming fears of adulthood. Putting mostly first-time actors like Sasha Lane amongst familiar faces like Shia LaBeouf (a revelation here) and Riley Keough, Arnold takes us on a road trip across the forgotten towns of middle America without ever indulging in smug Hollywood archetypes or the poverty porn of modern American indies. Instead, Arnold creates a blistering vision of America and its societal and economic failures, shedding light on generations of neglected Americans living in poverty.Arnold understands the broken class system in America. “American Honey” isn’t a neoliberal fantasy of middle America or a boomer’s spiteful depiction of younger generation’s economic hardships. It’s a passionate love letter to a misunderstood generation facing an uphill battle they’re not entirely prepared for. But despite Arnold’s unwillingness to let us forget the harsh realities of the economic climate they’re living in, she still infuses the film with a buoyant hopefulness that younger generations could use a whole lot more of right now. — MR

32. “First Man” (2018)

Director Damien Chazelle and screenwriter Josh Singer eschewed expectations of an inspiring space epic in the vein of “Apollo 13” with this subdued, surprisingly mournful examination of mid-century virility and America’s soulless, capitalistic quest for innovative domination. Like other Chazelle protagonists, Neil Armstrong is an obsessive driven by the very American concept of greatness at all costs, but this time the filmmaker puts that obsessiveness under a microscope and examines it through the lens of grief. Taking a bit of creative license, Chazelle uses Armstrong’s mourning as a catalyst for his workmanlike obsession with a remarkably tactful and honest perceptiveness. Ryan Gosling is brilliant as Armstrong, deftly capturing the reticent masculinity of the era, while resisting the urge to imbue Armstrong with a warmth he notoriously lacked. It’s always difficult to predict the shelf life of a film, but “First Man,” terrifically visceral and thrilling in its stupendously crafted action sequences, and achingly melancholic in its notions of letting go, feels like an ideal candidate for future rediscovery. — MR

31. “High Life” (2019)

The agonizing cost of occupying a human body is one of the central themes of Claire Denis’ thematically gnarled, existentially disconcerting, and wholly unclassifiable science-fiction odyssey “High Life,” which is more preoccupied with bodily secretions than a Farrelly Brothers movie. Denis is, among other things, a poet of perversity, and “High Life” marries the downcast gloom of “Trouble Every Day” with the nonlinear visual poetry of her great “Beau Travail” while still managing to feel like nothing else in her filmography. “High Life” is the story of a group of convicts who have been exiled from earth and forced to live on a floating space vessel hurtling toward some vast interstellar chasm. At its core, however, Denis’ most ferocious film to date is a hymn-like parable about human’s inherent capacity for savagery – and how transcending that savagery is what makes us more than just sentient animals. Robert Pattinson commands the central ensemble with one of his most reticent turns to date, but regular Denis regular Juliette Binoche is also worthy of mention as a horny, demonic doctor who treats her human patients like sexualized farm animals. – NL