I first watched Mantan Moreland when I was a teenager. My father (born in 1941) grew up on the Charlie Chan series in which Moreland played a Black, nervous, jumpy, and bulging eye assistant to the fortune-cookie accented “Asian” detective (who incidentally, through Sidney Toler’s portrayal is an example of yellowface). I didn’t know why at the time, but Moreland’s performance for some reason hurt me—and I couldn’t understand how my father could be watching these tasteless low-budget films. It wasn’t until I saw Spike Lee’s controversial and daring masterpiece “Bamboozled,” which Criterion gave a re-release to this April, that I understood why my dad laughed out loud to Moreland and why I should have had some empathy for the near-impossible position Black comedians like Moreland found themselves in before and during the 1940s.

“Bamboozled,” Lee’s 15th film, arrived at an inflection point: Timed to the nearly hundred-year anniversary of cinema and the fiftieth of television. By this point, Lee had already witnessed his generation’s Black wave of cinema fizzle, overtaken by white creatives hoping to replicate Black narratives without the former’s nuance. Moreover, Black variety shows and sitcoms like “In Living Color” (1990-94), “Martin” (1992-97), “The Wayans Bros” (1995-99) had come to an end. In short, Lee made “Bamboozled” as a commentary with these trends and this history in mind.

READ MORE: Spike Lee’s ‘Jackie Robinson’ Is A Complex Biopic That Needs To Be Made

His satire follows Pierre Delacroix (Damon Waynes), a self-refined patronizing Black television programmer intent on making his mark. Jada Pinkett Smith plays his assistant, Sloan Hopkins, while Michael Rapaport portrays Delacroix’s boss, Thomas Dunwitty. Surrounded by pictures of Muhammad Ali, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, etc. in his office, Dunwitty fashions himself an expert on Black culture—even surmising that he’s Blacker than Delacroix. The distasteful Dunwitty routinely drops the n-word on a whim and wants Delacroix to create a show that’s Black yet marketable to white audiences; a program he believes should lack nuance and stimulating narrative frames, repeating the media’s representation of Blacks from the last fifty-plus years.

Like Max (Zero Mostel) and Leo (Gene Wilder) in “The Producers,” Delacroix believes he can game the system. He wants to create a show racist enough that it’ll horrify white and African-American audiences alike to the point of cancellation, proving to television executives their ignorance with regards to Black culture. He recruits two poor African-American street performers—the hoofer Manray (Savion Glover) and his hype-man Womack (Tommy Davidson)—to don blackface and change their names to Mantan (a reference to the real-life actor) and Sleep ‘n Eat (an allusion to comedian Willie Best)—to star in a show entitled “Mantan: The New Millennium Minstrel Show.”

Lee, through Delacroix, sketches the fictional production to be shocking yet conflicting. For example, Mantan and Sleep ‘n Eat are depicted as slow and obstinate buffoons who reside on a watermelon plantation. Furthermore, the program also employs a house band called The Alabama Porch Monkeys (played by The Roots) and is filmed in front of a live studio audience—owing to the theatrical roots of the minstrel. From the Criterion edition’s supplementary material, in an interview with esteemed-film critic Ashley Clark, Lee reveals that the filmed audience was composed of extras who were given no prior warning they were going to be shown a minstrel. As the footage of the crowd demonstrates, many were unsure how to react: Some laughed while some were appalled, as they watched Mantan revive an unconscious Sleep ‘n Eat with the allure of a giant watermelon.

As viewers, Lee puts us in the same crucible too. For instance, there’s one sketch where Manray and Sleep ‘n Eat employ Indefinite Talk; an act where the two respond to each other’s sentences without ever completing their thoughts. The performance is fantastic, amusing even. But upon remembering the setting and the use of blackface, viewers come to question why such a routine elicited laughter, to begin with. “Bamboozled” thrives on those instances, demonstrating to us the pervasiveness of the imagery and the psychology of its humor. Indeed, I wonder if my father laughed at Mantan in “Charlie Chan” because he sensed the humor’s uneasiness: If he howled because he knew how talented Black comedians like Mantan had to be to pull off these stereotypical roles. I wonder if it ever stung my dad to see men like Mantan relegated to these maligned characters and if it matters if it didn’t.

Audaciously, Lee never fully denigrates the minstrel: a decision that might seem schizophrenic to some considering the satire’s intent. Ruth E. Carter’s lively costumes for the minstrel performers are composed of an array of beautifully matched vibrant colors and palettes. The dance sequences, which utilizes’ the director’s wonderful eye for MGM musical sequences through his reliance on full-shots with positive and negative space and filmed on 16mm, demonstrate the artistry at play by the performers. Most importantly, in a compelling scene where the actors are in street clothes practicing their dance routines, Lee shows the determination and hard work required for Black minstrel actors to perform these sketches.

The complexity of Lee’s views on blackface is a context that I’m not quite sure even a phenomenal critic like Roger Ebert understood when he used Ted Danson’s use of blackface as an example of the inherent wrongness in applying the practice. Because with Black actors like Bert Williams, who participated in minstrels during the 19th and 20th centuries, their performances possessed an inherent level of professionalism and understanding of how to undermine these stereotypes. Furthermore, actors like Mantan and Williams had fewer avenues to pursue their dreams; so if they had to blackface or rely on stereotypes, they still had to do them well. Especially Mantan, who was disposable in the Hollywood studio system and could be replaced by a cheaper Black comedian at any moment.

“Bamboozled” finds greater complexity through Delacroix, even if the character’s intent appears unclear. One of Lee’s few missteps: Is Delacroix conducting this risky experiment for the good of the community or for his own ambitions? Though he relates to Sloan his hope that the show will fail and he’ll be let out of his contract due to its cancellation, he also gives a spirited defense against stereotypes when Dunwitty re-writes his scripts. With Delacroix in mind, “Bamboozled” examines the definitions of Blackness by both Black and white people. To both Sloan and Dunwitty, Delacroix isn’t Black enough. Moreover, the television programmer modulates his Blackness to survive and succeed in the white-dominated television network, from his manner of speech to his name (his given name being Peerless Dothan).

Manray and Womack do not fit the stereotypical definition that white audiences have of Black people either. It’s why, though talented, they languished as street performers. In fact, Lee even takes time to make a through-line from the minstrels of prior centuries to the hip hop music videos of today. With this in mind, in order to appeal to white audiences, Manray and Womack must “Blacken” themselves up into caricatures through their blackface makeup and by confirming racist clichés. The fact that Delacroix doesn’t realize the appetite white audiences have for this form of “entertainment,” especially considering he’s been self-modulating to fit within the white milieu, is the great irony of “Bamboozled.” It demonstrates how far he’s removed himself from his Blackness, and further opens the question: Who’s getting bamboozled?

In fact, in one of the narrative’s most poignant scenes, Delacroix visits his father Junebug (Paul Mooney). A once-famous stand-up comedian, and a metaphorical example of Black performers from generations past, Junebug now tours the chitlin circuit after refusing to moderate himself to white audiences and powerbrokers. The people with green light authority, the ability to approve shows and talent, don’t understand him and his audience. For that reason, he defies them. When Delacroix sees his father, he thinks he sees a broken man—not an artist simply happy with his freedom. Delacroix begins to associate Blackness and independence with failure. He chips away even more portions of himself. It’s a heartbreaking sequence in an otherwise zany film that relates to the struggle many Black creatives have today: How much of your essence will you still have when you finally make it?

READ MORE: Jury President Spike Lee Agrees With Cannes Postponement: “We Are In A War-Like Time”

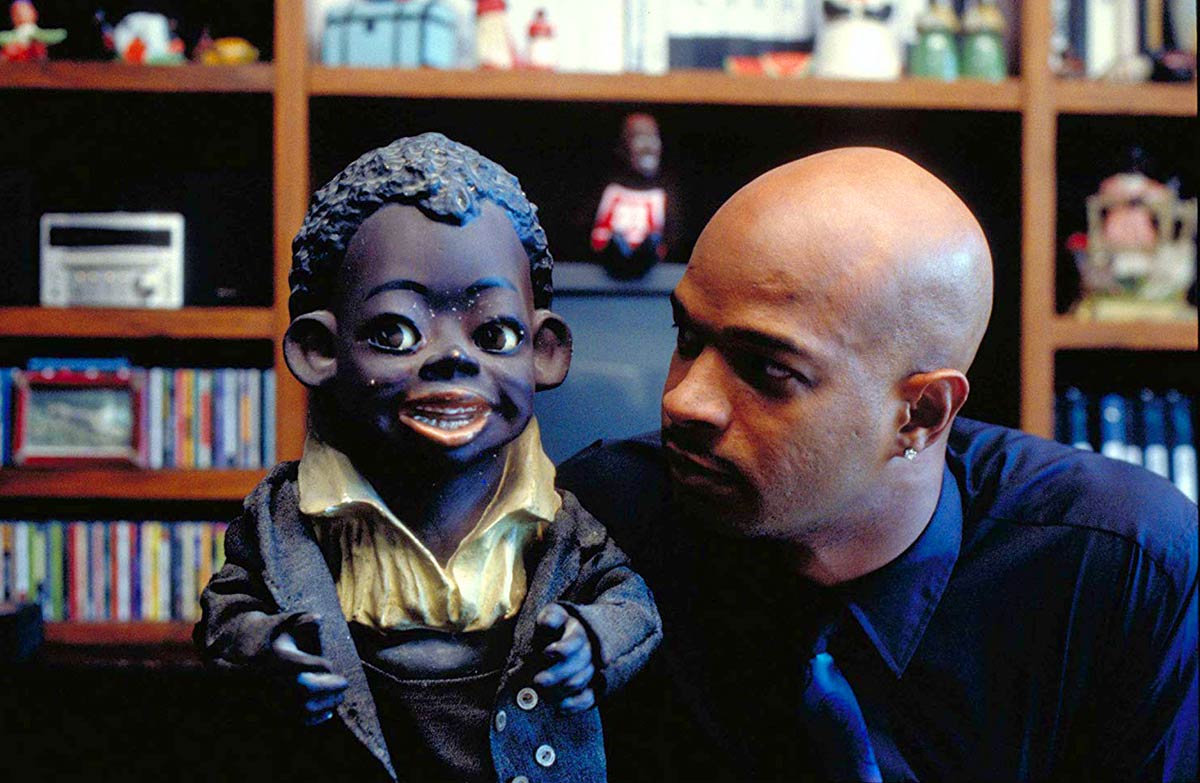

Consequently, both Manray and Womack are slowly crushed by the emotional toll required to don their blackface. Womack sheds a tear whenever he applies his make-up and soon realizes he doesn’t recognize himself anymore. Worst yet, with an entire Black community up-in-arms, a militant group kidnaps Manray for public execution by webcam. In 2000, like much of “Bamboozled,” the scene probably felt improbable, at best. A Black man whose on-camera death becomes a cultural focal point? A few short years later, the sequence would become frighteningly prescient. By the satire’s end, now surrounded by Mammy miniatures, lawn jockeys, and minstrel mechanical banks in his office, Delacroix dons blackface himself. Emotionally devastated and drained, it’s a fascinating moment that I’ve never been able to completely decipher. It’s as if Delacroix could only feel the pain many other Black creatives have felt when choosing to sacrifice one’s identity for the narrow path of success by physically “blackening” himself-up. Not a mistake by Lee, but murky nonetheless especially considering it resides during an odd tonal shift toward the melodramatic.

Lee concludes his satire with one of the most poignant sequences of his career; a montage of blackface through the decades: from cartoons to Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland employing the despicable practice—set to Terence Blanchard’s sincere and elegiac score. It’s a gut punch that still plays as an unflinching cultural soliloquy, today. It reminds me of the brunt of images my father probably witnessed for much of his life, and why laughing at Mantan didn’t seem so bad to him.

Unfortunately, only now has “Bamboozled” begun to have a little less relevance. If only because there’s been a renaissance of Black cinematic art. Nevertheless, African-Americans still lack “green-light” authority, which makes Black art remain partly at the beckoning of white network heads. Nevertheless, twenty years later, “Bamboozled” ranks alongside “Do The Right Thing,” “School Daze,” and “Malcolm X,” as one of Lee’s most intricate, controversial, and regrettably timeless masterpieces.