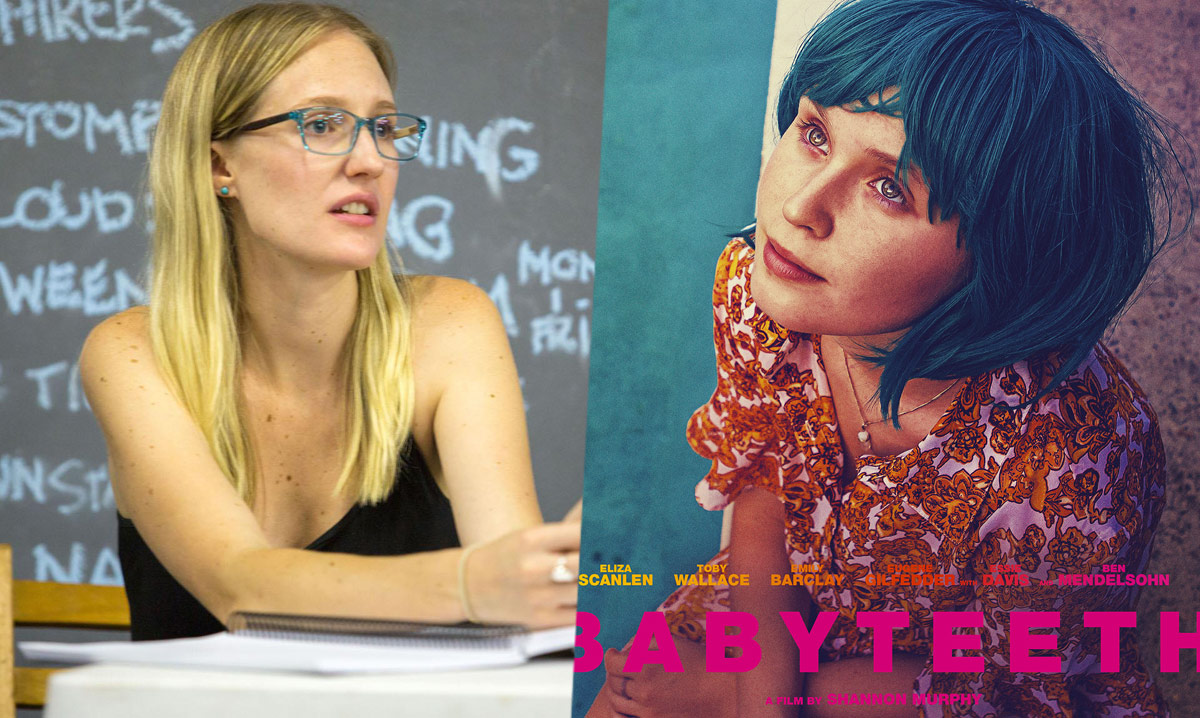

If 2020 manages to match a feature film debut as electrifying, devastating, hilarious, and original as Shannon Murphy’s “Babyteeth,” it will mark one of the strongest years in breakout director discoveries in recent memory. However, it seems highly unlikely. The Australian director and her screenwriter, Rita Kalnejais (making her screenwriting debut with the adaptation of the play she penned in 2012) have crafted a story both supremely relatable and utterly singular.

“Babyteeth” follows Milla (Eliza Scanlen coming off her stellar American feature debut, “Little Women” and a breakthrough performance on HBO’s “Sharp Objects“), a terminally ill Australian teen coming-of-age in a tight-knit three-person family. Her father Henry (Ben Mendelsohn) is a psychiatrist, and her mother Anna (Essie Davis) is a retired piano master. She lovingly calls them by their first names. Henry writes prescriptions for him and Anna (barbiturates, amphetamines, and the like), but, reasonable, presentable, and friendly as they are, they don’t seem as if they are guzzling pills behind closed doors. That is, except for when they get a bit too high at dinner.

READ MORE: 52 Films Directed By Women To Watch In 2020

An already impossible situation in Milla’s illness is complicated by the fact that a late-20-something street rat named Moses (Toby Wallace, who picked up acting awards in Venice and Marrakech for his performance) steals Milla’s teen heart before he starts stealing her parents’ drugs in the middle of the night. But his shameless betrayals are never enough to topple Milla’s bottomless well of forgiveness, which creates a situation in which her parents are forced to either cut her off from the jerk or abandon all parenting advice for the sake of their daughters’ only romance.

Despite being a film about how a family deals with youthful terminal illness, “Babyteeth” is nothing like the typical fare of that ilk. This is not the pure agony of “Lorenzo’s Oil” or even the eccentricity-meets-chemotherapy that is “Me, and Earl, and the Dying Girl.” An equitable blend of complex themes that deal with corrosive heartthrobs, suburban family dynamics, the preciousness of life, the soulful significance of music, the universality of lying, and more, “Babyteeth” is in its own subgenre of sorts.

READ MORE: 100 Most Anticipated Films Of 2020

In other words, it’s the kind of film that carries singular confidence and poignancy that must be seen to be believed. And if it’s any indication of the career to come for Murphy, she will soon become one of the most discussed and adored working directors. I was able to speak with Murphy and Scanlen about what it was like to create what is easily one of 2020’s strongest offerings so far.

READ MORE: The 25 Best Movies Of 2020 We’ve Already Seen

The family dynamic in ‘Babyteeth’ is so different from any other I’ve seen on screen. What was it like creating and living into a family where everyone is equally fucked up, falling apart, and self-medicating?

Eliza Scanlen: It’s a fly on the wall kind of film of the life of a family dealing with teenage issues, but it’s exacerbated by serious illness that they now have to navigate. I think it’s so heartbreaking that the parents don’t know what to do with themselves. I think Milla can live the time she has remaining and once she’s gone, she’s gone. In a way, she has this resilience. But everyone in the ensemble has something they need to fix, and they’re all medicating in some way. And I don’t know if they do it successfully, but they do try to help each other. I think we’re often met with caricatures of a dysfunctional family and it’s not usually that truthful, whereas this feels really real and like something that a lot of families can identify with, especially when a young teen is beginning to understand what independence really means.

Shannon Murphy: And I’ll say, too, what I really want to focus on in order for them to not feel like caricatures. The addiction everyone is dealing with…you come out of this experience feeling like you understand it more than having judged it, and I really wanted the tropes of, say, the drug addict boyfriend or the mum who pops pills – that all of those were given an honest voice and a human behind that trope that we’ve seen many times before. Because I think it’s easy to dismiss people, or hate their way rather than really get to the heart of why they’re doing that and have empathy for them.

Did you intentionally challenge the concept of a tiered morality between parent and child? Where parents are always right, and kids are always wrong.

SM: I love the morality question. There’s only been one other journalist who’s brought up morality. To me, that is such an American theme that runs through so much of your cinema. What I hope is that American audiences – who, you know, do have a really strong moral barometer about things – can still enjoy these characters that fall into an amoral category, though you still love them and understand them.

Speaking of the American perspective, one of the lines that stuck with me most was “Fuck the tiny gods in your head,” which is how this movie feels so much of the time. Fuck what you think about God, about family, about morality. In the film, everyone’s priorities have changed so drastically. It begs the question: would this family operate in a similar way if Milla didn’t have a terminal illness?

SM: I kind of do [laughs] in some regard. But not to the extent that we’re witnessing, because these are people in crisis, everything’s heightened, and they fall more heavily on their vices. But I do think that, you know, these aren’t people behaving in a way they’ve never behaved before. To some degree, yes. Chiefly for Milla. I think Milla is…well, Eliza, you might want to talk to that.

ES: Yeah, I agree with you. It definitely is heightened, and I think for that reason it’s a case war of attraction in a way. I think she’s attracted to Moses for a reason. The only way it came about, to begin with because of its transactional nature. They were both getting something from each other. He wanted drugs from her, and she wanted a case of independence and freedom and someone to run off with. But no, I don’t think that Milla would’ve been as daring if, well, you know, we meet Milla at a time where she’s going through the relapse of her parents, she doesn’t remember a life without terminal illness, and all of that has to have some kind of an impact on her personality and her life. If you’re asking what she’d be like, or what the family would be like, without terminal illness affecting them at all…I’m not quite sure. Maybe they’d be totally different.