Get ready to get very, very paranoid. Just in case you’d begun to regard your laptop or the mobile device on which you’re reading these words as a benign contraption whose primary covert function is the ability to snap quickly to a spreadsheet when the boss walks by, here comes Alex Gibney, on prime Gibney form, to shatter that cozy illusion and make your world feel a lot less safe. His new film “Zero Days” may ostensibly be an investigation of the 2010 malware worm known as Stuxnet, but over its swift-moving 116-minute runtime, Gibney does a much broader and more important job: relating the rather airless, abstract concepts of cyber-terrorism and internet espionage to their real-world consequences. At the start of the film, the pronouncement made by one interviewee that the Stuxnet attack could be likened to Hiroshima in its introduction of an unprecedented new category of weapon that will usher in a new age of international relations might have seemed like hysterical hyperbole. At the end of it, it seems like understatement. Here be dragons.

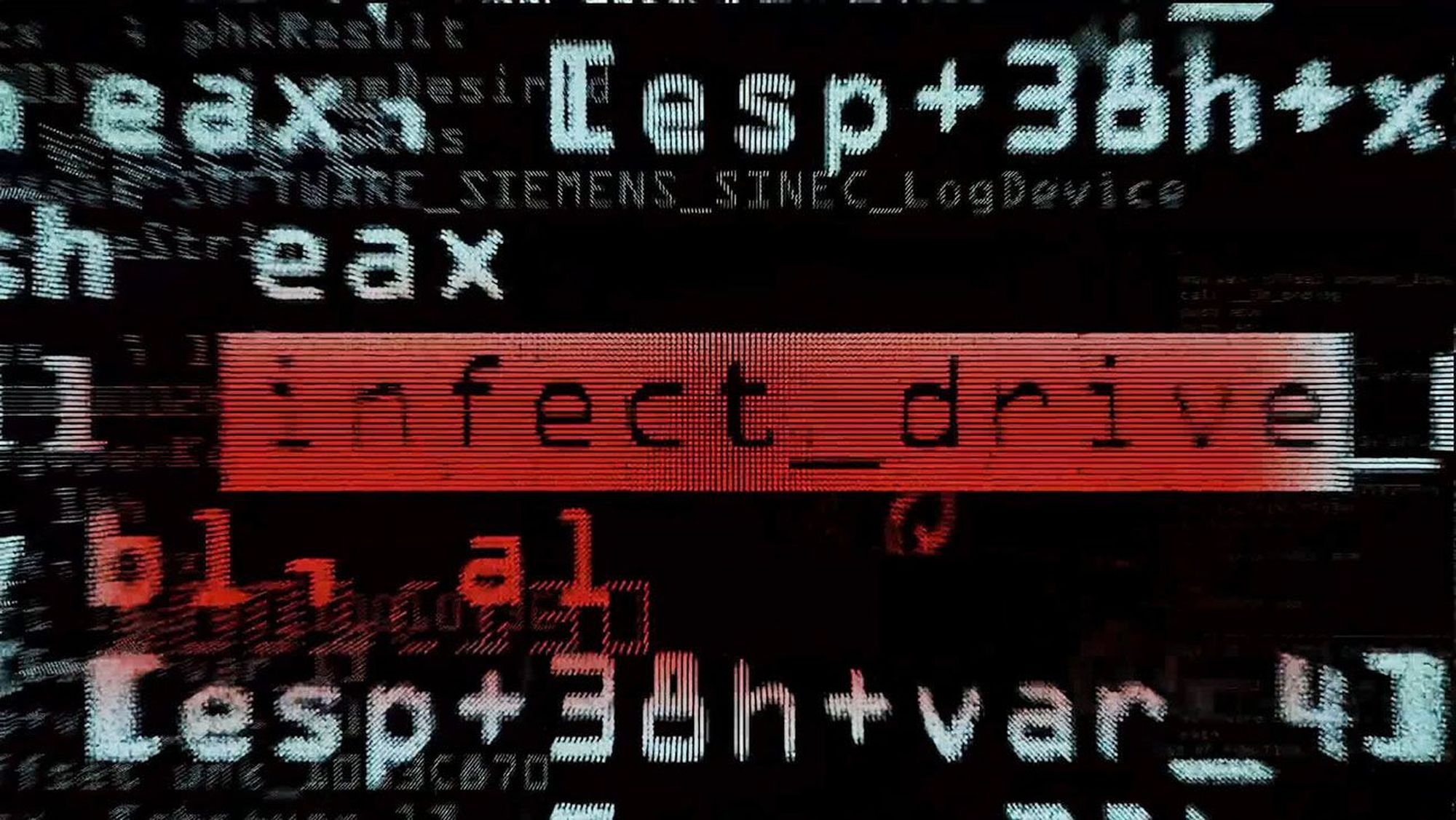

Stuxnet was initially detected in Belarus, and then started popping up on computers all over the world. It puzzled security analysts because of its sophistication and how good it was at hiding not just its origin, but its intended target. Quickly establishing that the code was simply too clean, complex, and clever to be the work of even the most talented hacktivist or online fraudster, security firms like Symantec and Kaspersky almost immediately suspected it had to have had “the resources of a nation state” behind it. Two Symantec sleuths (Eric Chien and Liam O’Murchu) dedicated months of all-nighters to unpacking the code and ultimately deduced it was created solely to target certain Siemens devices, such as, oh you know, the ones used to control the centrifuges that powered Iran’s controversial nuclear energy program.

There is such a wealth of cleanly delivered, case-building information here that there’s no room to do it justice. But as well as talking to Chien and O’Murchu, and other private security engineers, Gibney secures some really stellar interviewees outside that industry. Iranian experts, nuclear scientists, and Israeli security insiders all contribute vital pieces of this vast mosaic, while most impressively (and engagingly, because he comes across as bizarrely likable), Gibney interviews General Michael Hayden, former head of both the CIA and the NSA. Hayden talks surprisingly candidly about the geo-political implications of Stuxnet, while still evading direct questions about it due to its “hideously overclassified” nature. Along with the segments with David Sanger, the New York Times journalist who first broke the story, all these contributors combine to provide an impressively detailed helicopter view of the vast, exponential consequences of a covert operation that ultimately only slightly dented Iran’s nuclear capability, and indeed led to them developing their own “cyber army.” This is our slightly terrifying new world order in which, with the fateful predictability of an Orwellian nightmare, the cyberweapon the U.S. developed can now be used against it, and the U.S. won’t even have moral grounds to oppose it.

Gibney’s style has come to define this kind of investigative documentary, and he certainly doesn’t do much formal reinvention here. His authorial imprint, if you can call it that, has always been relatively invisible (though here there are a few moments of his voiceover, usually expressing frustration over the high-level stonewalling that goes on around the topic). But while the talking heads + tv footage + recreations + graphics formula he has perfected has simply become the handiest lexicon for telling this kind of story, there are elements here that feel tired. Injecting dynamism into visually staid interviews by using a handheld camera that constantly reframes the subject has become kind of obvious, and the “Matrix“-y graphics designed to represent reams of un-cinematic code, the montages of hands pressing bright red buttons and a bursting balloon cut against a mushroom cloud feel similarly overworked. That said, other flourishes work well, like the one interviewee (and the film’s sole female voice) who for the sake of relative anonymity — with a small reveal later on — is essentially rotoscoped into a vectored, bitmapped version of herself.

Though formally unadventurous, it is put together with intelligence — a quality Gibney also credits to the attentive viewer by keeping overt explanation of the jargon-heavy terminology to a minimum. But one exception is the term that gives the film its title: a “Zero Day,” we’re told, is a valuable piece of code that essentially allows malware to operate without the target user knowing or doing anything — no downloading a file, no rebooting, no clicking on a link that tells you that someone finds you really attractive.

Another term that crops up is “air gap.” This is the putative jump that information has to make in the real world, from wherever it’s stored on the internet to a more secure, closed-circuit network, such as that which controls Iran’s nuclear program. Historically, that has necessitated the use of real-life spies who have to get the malware into the system using “Mission: Impossible“-style tactics. But Stuxnet (and why does it have to sound so horribly close to the apocalyptic Skynet from the “Terminator” movies?) in its latter, more aggressive stages was designed to defeat the gap without anyone having to dress up as a cleaner and stick a USB key into a computer. It worked, but at the cost of its own detection. And now the cat can never go back in the bag.

The sudden realization by nations everywhere that there is a new, unpoliced and legally gray battlefront in international politics has led to an official policy of deafening, paralyzed silence while everyone looks at everyone else to see who’ll fire the next volley. With “Zero Days,” Gibney does a great job of breaking that silence and of bridging a different “air gap” — the one that exists in our minds between remote, antiseptic-sounding terms like “malware worm” and the real, physical world. This weapon has the power not just to slow centrifuges, but to destroy banking systems, to down power grids, to crash planes, to launch rockets, to kill. It’s already out there, and no one’s allowed to talk about it. [B+]

This is a reprint of our review from the 2016 Berlin Film Festival.