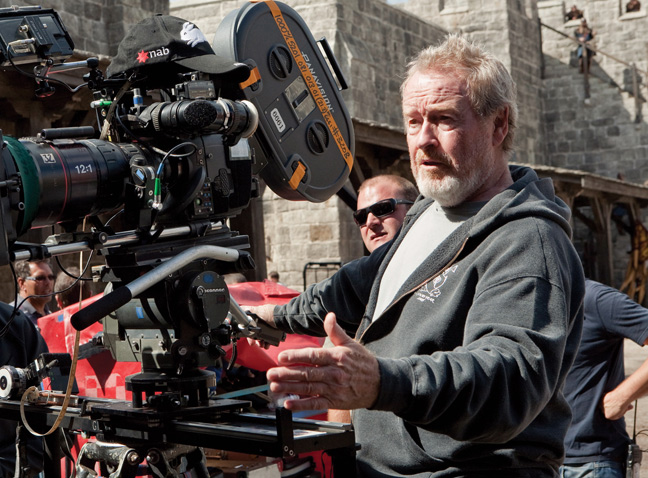

Ridley Scott may be getting up there in age – he turns 78 later this month – but the man is much more prolific now than when he was just starting out, and some would argue his latest film, “The Martian,” is right up there among his best work. Within this past week, it actually became the highest grossing film of his career, crossing the $200 million mark domestically.

Ridley Scott may be getting up there in age – he turns 78 later this month – but the man is much more prolific now than when he was just starting out, and some would argue his latest film, “The Martian,” is right up there among his best work. Within this past week, it actually became the highest grossing film of his career, crossing the $200 million mark domestically.

So, now seems like the perfect time to hear him talk about his career, and at the AFI Film Fest this past Wednesday, that’s exactly what happened. Moderated by Variety’s Scott Foundas, Ridley Scott talked for nearly an hour, going into great detail about how he wound up making “The Martian,” and discussing his other notable films, including “Alien,” “Blade Runner,” and “Thelma & Louise.”

Moreover, Scott recounted a number of humorous anecdotes, including how back in his early days when he worked for documentarians D.A. Pennebaker and Richard Leacock, or the time when he found himself doing pre-production on a film with The Bee Gees. You can check out some highlights of the conversation below and/or you can listen to the entire conversation at the very end of this article. Here are some highlights from the talk.

What Interested Him About “The Martian”

A film like this has got a big crew, fantastic cameraman, great actors… that said, the director is where the buck stops. That said, the book is terrific and the author’s a real pistol. He and the writer who adapted the book, Drew [Goddard], kept in place the fact that the book is very amusing.

So, it’s not a thing you expect, if you haven’t seen the film – go and see it – it’s really amusing, but the humor is derived from, fundamentally, his predicament and how he deals with life, where he’s gonna have to stay alive for four years. And of course, having Matt Damon is an advantage, right? He’s wonderfully amusing serving very dry humor, which works very well, because the whole body of the humor lies in what was written, as voice-over. And he and I were kinda concerned about — a lot of voice-over will wear out, I don’t care who it is — so we had to invent how he speaks and he can’t just speak to himself. So, a very simple thing comes up, I brought out 30 GoPros, teeny cameras, so if I’m sitting here in my habitat and I’m reading data, working out how I’m gonna stay alive for another year and I start to talk — I’m actually talking to a GoPro that could be there or could be behind me because in this habitat, like any good black box on an aircraft, a GoPro is gonna record the moment you died and why. So there’s a technological logic to it as well. Suddenly, the GoPro has become a buddy so the voice comes alive as a secondary character.

Drew had written [the movie] for himself…and… he said, “I wrote it and then I decided I didn’t wanna do this and I thought of you,” which is very sweet and that’s what happened.”

How He Got His Start

My career [started] in art school and art school was everything to me and my school years were significant. So I still use everyday what I learned in art school all that time ago. I was at Northern Arts School which was a small arts school, but then I [attended] Royal College of Art — both places were special and I learnt everything there. I learned — most important of all — that I got a very good eye and a good eye works great in commercials, and I had a pretty significant career in commercials. A long time, almost 30 years. During that time I was sharpening my skill of speed operating. I love to camera operate so I was operating all the commercials, really. And it makes you think on your feet, it makes you think visually. You combine that with being able to draw — and I can really draw — and I would [story]board everything, I would board the commercials.

My first job out of college, I was given a traveling scholarship – because I was a very good designer – and I went off to New York on a traveler and design scholarship. I went down to the streets of Madison Avenue and Lexington, trying to get a job as a photographer or in design, I was drifting towards design. I knew there were two great documentarians called Donn Pennebaker and Richard Leacock. I tracked their offices down [and] it was smelly, it was nasty. I stood there with my seven years of work, my portfolio, in this narrow hallway. I stood there for two mornings. First morning, I stood there at 11 o’clock and they aren’t coming. Next morning… I sat there looking through the steamy glass and saw these two guys get out of a cab and I knew it was them.

So I hopped out, got the student portfolio, struggled down the corridor behind them, and there’s an elevator the size of this chair. They got in and I said, “Can I come in?” And so I got in, and I’m standing there. By the time I got to the 3rd floor, I had a job. Doors close and I said, “You don’t know me and I don’t know you, blah blah blah.” They got out [of the elevator] saying, “Get out,” and then they said, “Should we give him the job?” and I think Pennebaker said, “Let’s give him the job.” So I got the job. I then spent 7-8 months syncing up rushes, watching Jack Kennedy beat Hubert Humphries in the primary… then I was told by the BBC, “Get your ass back here, you can’t keep the job.” So I was back at BBC. I designed there for three years. In that time, I loved the process of design, I buried myself in design and then found an outlet, I wanted to get into advertising. [And I did] a little commercial for Gerber’s baby foods.

Then, when I came to do my very first film, and I didn’t do a film til I was 40, I suddenly thought, “Geez, I better do something or it’s gonna be too late.” And at that moment I could afford to look around, pay for a writer myself, naively choose a subject I never knew would ever play anywhere, but I chose “The Duellists” and I was very proud of it. And we won at Cannes and so I thought, “Wow, that was easy.” [laughs]

Getting Killed By Critics And Pauline Kael

Getting Killed By Critics And Pauline Kael

I was so beaten up early on by critics, who criticized “The Duellists,” killed me on “Blade Runner,” absolutely slaughtered me. And it got personal. Somebody accused me of growing a beard because I had a weak chin and I was like, “What?” And I’d never forget it — that was Pauline Kael. And I thought, “I’m never gonna read another critic again.” And I learned from it. I’m a painter. Every morning you look at the painting and you have to analyze what’s wrong with it, or if it’s good, move on. And so when you make a movie, you have to be your own critic. If you’re not, you shouldn’t be doing the job.

Learning To Work With Actors

I was frank with actors because they’re doing this mysterious thing called acting. Took me about ten years to get over that. Then, I realized the next phase ought to be a partnership, the best arrangement with an actor is a partnership. But in the partnership, somebody actually has to know what he’s doing. What film schools don’t teach students is, there’s a second hand doing this [“clock ticking quickly”] and the other hand is a dollar sign. So you better move on knowing exactly what you are doing. And I learned that from storyboarding. I shoot it on paper in my head before I get to the shoot. Now, actors would say, “Yeah, but that doesn’t give me any room to move because you storyboarded so you pre-decided what I’m gonna do before I get there.” And my answer is, “Absolutely.” Because it’s better somebody knows what they’re doing as opposed to saying, “Let’s have a run in this room” because the [clock] is ticking. But I’ve also discovered that actors love to have people who are in charge to be decisive…they can sense confidence. If you’re not confident, you’re gonna have a horrible time.

Influential Movies

I was in Hartlepool, there was an Odeon Cinema…and I would spend every Saturday there…my fodder…would be anything that’d come out of Hollywood. There was no alternative cinema for me, there was no foreign cinema where I could watch good and highly pretentious films, right? So I watched every goddamn thing that came out of Hollywood and, you forget, I watched “Singin’ in the Rain” recently and it’s a fantastic film. You know, dancing at that level – that’s Olympic, it’s so stunning. Everything about it is so well done, thought through, analyzed, cunning, everything.

The thing I was completely enamored with was [the] western. I think I saw every western under the sun and still one of my favorite westerns is “The Searchers,” which anyone will say, “Well actually, ‘The Searchers’ is incredibly wrong in every possible way historically, for a start, Indians don’t wear war bonnets…” And I’d say, “I don’t really give a shit.” And then, the evolution of that was magic cause London, to me, certainly was magic and they had the National Film Theatre. So I’d live in the National Film Theatre, and on a student ticket I could get in for nothing. I’d get a bottle of beer, pack of cigarettes, and I’d be in there every night. I think I watched every Ingmar Bergman film. And every Kurosawa. They became the main fodder for me. The closest I’d been to a director was John Cassavetes. Cassavetes didn’t know, but I had stood right behind him – I didn’t dare speak to him – but he was running “Shadows” and I was standing in the queue and it was dark and wintry, and I saw this guy walk out and look up at this awning in the theater and I thought, “Holy moly, that’s John Cassavetes.” And I loved what he did, so I became very Catholic and I didn’t know, really, what to do other than the fact that I just loved that flickering screen.

Working On “Alien”

Somebody mysteriously said, “This guy did ‘The Duellists,’ maybe he can do ‘Alien.’” I failed to see the connection. I know I was the fifth choice, they were getting desperate. I was after Robert Altman. Now why would you send Bob Altman? That was really stupid… But I was a designer and was steeped in Jean Giraud comic strips and “Heavy Metal” comics, which were pretty adult actually but were very interesting. And I was reading and thinking, “Holy God, I can apply all my design knowledge to this and I know just what to do.” So I was standing in Hollywood within 36 hours and, from there, they said the budget was $4.2 [million], I said, “Ok fine.” Never take your notes into a pitch because you will turn your film into a development deal. Never do that, just say you love it. Once it’s greenlit, you can change it then. I do it all the time. Somebody will overtalk it and you suddenly find yourself on the slippery slope of a development deal.

I went home, sat down, and I storyboarded the entire film right through everything because my boards aren’t stick figures… so I had to imagine what the ship is like, what the nasty little bugger that came out of the chest looked like. But I knew what the alien was like then because I’d seen the H.R. Giger book. I went back and the power of the board doubled the budget and I went from 4.2 [million] to 8.4, then I think I went over a bit at the end [because] they wanted to end the film when the door closed. I said, “You can’t do that. He’s in the shuttle.” And they said, “This is excessive.” And I said, “Excuse me? I am paid to be excessive, dude, it’s up to you to hold me down. If you can’t hold me down, you shouldn’t be hiring me.” And so, what’s it gonna cost? And so I said, “We’ll cost it.” So I take the shuttle, hang it from the roof, work out how I was gonna have engines blowing this thing off the ship. We shot that in five days and you saw the difference because, in effect, it’s the fourth act. Right? And that’s the power of drawing.