Acclaimed photojournalist Gordon Parks was something of a renaissance man. A photographer, writer, composer, film director, and activist—he imbued the American Black experience with a sense of gravitas, esteem, and pathos through his Black gaze. Referencing Parks’ same-titled autobiography, director John Maggio’s “A Choice Of Weapons: Inspired By Gordon Parks” showcases the famed photographer’s work for a new generation but does little to elaborate on the man incisively.

READ MORE: 2021 Tribeca Film Festival Preview: 15 Must-See Films To Watch & More

The “inspires” in the film’s title should be taken literally. The talking heads assembled by Maggio include contemporary Black photographers who’ve made their names documenting racial injustice, such as Jamel Shabazz (the prison industrial complex), Devin Allen (the Baltimore protests following the 2015 murder of Freddie Gray), and LaToya Ruby Frazier (the Flint, Michigan water crisis).

READ MORE: Summer 2021 Preview: Over 50 Movies To Watch

They explain how Parks shaped their respective callings and visual acumens. They also represent the cyclical nature of prejudice in America. The same topics Parks covered in his landmark photography series like “Harem is Nowhere” (1948) and “The Restraints: Open and Hidden” (1956) have cross-pollinated to their works. Likewise, directors such as Spike Lee and Ava DuVernay elucidate how he influenced their films, such as “Malcolm X” and “Selma,” respectively, through the unflinching intimacy he photographed his subjects with.

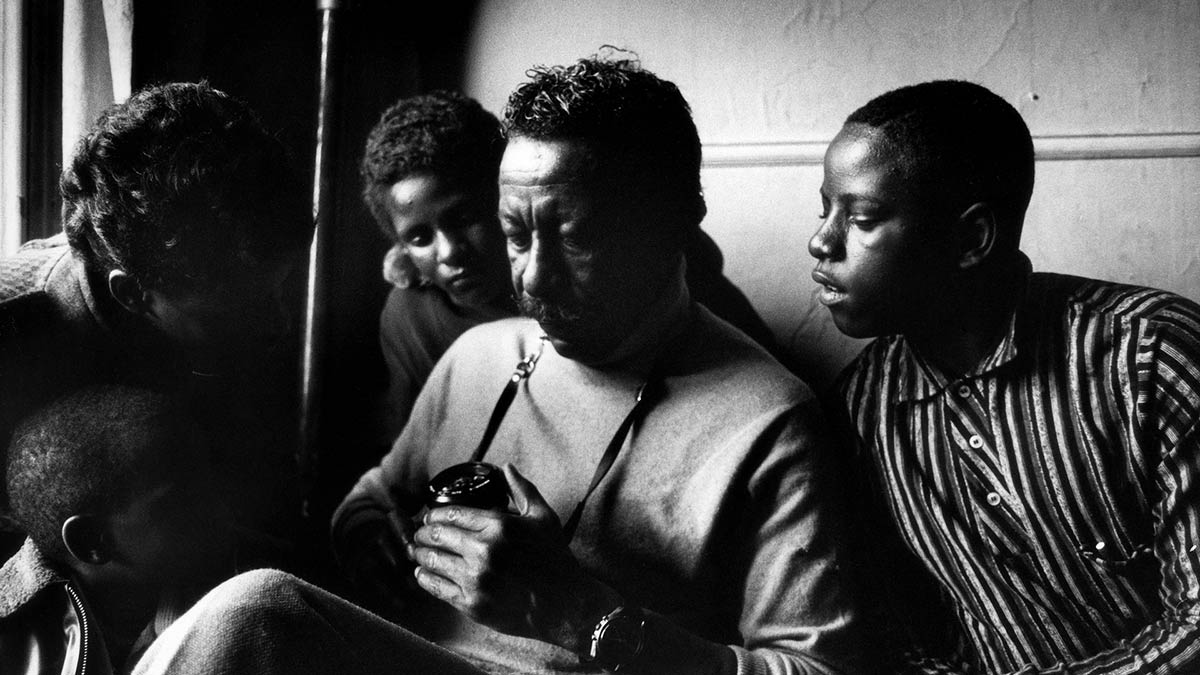

Maggio chronicles Parks’ life in great clarity: His unlikely rise from Kansas to his crisscrossing the nation as a waiter on a dining car of the Northern Pacific line to his final destination in New York City. Those new to the photographer’s work, like countless previous generations, will be dazzled to see his immersive, humanist black and white photography. His portrait entitled “American Gothic,” depicting Ella Watson, a government cleaning woman positioned by the American flag, offered a startling truthful commentary on race in America. It also introduced his calling card of embedding himself with his subjects, gaining their trust, and bringing out their innate spirit.

His later color photography amazes with the same yet distinct measure as his black and whites. At times, the use of color created a more abrupt juxtaposition of race relations than black and white could achieve. Maggio also covers Parks’ many famous subjects: Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, Ralph Ellison, to name a few. Along with the little-known people he came across. The film truly offers a comprehensive look at the photographer’s way of working, along with his work.

For a photographer often lauded for how intimately he captured his subjects, however, Maggio’s documentary is oddly distanced. Maggio relegates Parks’ personal life, for instance, to a few scant details. The director’s clear decision to aim for Parks’ overriding legacy would suffice if he didn’t unwind tantalizing threads along the way. Anderson Cooper briefly hints toward his mother Gloria Vanderbilt’s romantic affair with the photographer. But Maggio quickly changes the subject. In fact, I needed to do a quick Google search to figure out what Cooper meant in his digression. Likewise, Parks’ daughter and his ex-wife Genevieve Young both appear. Still, their fleeting screen time only allows them to explain that “Shaft,” the breakthrough Blaxploitation film Parks directed, was somewhat based on him and that he was a workaholic.

The film also exceptionalizes the photographer through its cursory examination of race within white spaces. The blind spot makes for a head-scratcher because, at one point, the New Yorker staff writer Jelani Cobb explains the paradox Parks occupied while crafting his debut film: “The Learning Tree.” By being great in multiple disciplines, the perception of him being exceptional segregated his triumphs from his race. Though Maggio acknowledges that truth, he commits the same error. Parks was the lone Black photojournalist at Life Magazine. He perpetually oscillated between both Black and white spaces. We certainly see how his works navigated these different cultural tonalities, but we see nothing of how Parks the person did. That’s the grave limit of relying on talking heads who didn’t really know him and limiting those actually did.

With his fascinating documentary “A Choice of Weapons: Inspired By Gordon Parks,” Maggio wonderfully lays out the importance of Parks’ work in changing hearts and minds, and cultures. But the vision of the man beyond his legend remains blurred. [B-]

Follow along with all our 2021 Tribeca Film Festival coverage here.