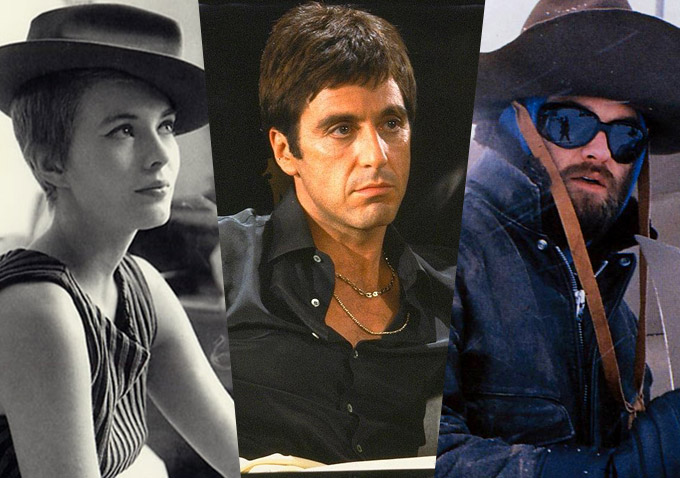

Original: “Scarface” (Howard Hawks 1932)

Remake: “Scarface” (Brian de Palma, 1983)

Five decades before Al Pacino said hello to his little friend, and Brian De Palma stirred up a major controversy about the violence and graphic bloodletting of his Oliver Stone-scripted film (written in cocaine daze, by all accounts), director Howard Hawks also ran afoul of censors with his original version of that same story (based loosely on the 1929 novel of the same name, which was inspired by the life story of Al Capone). In fact, Hawks’ “Scarface” was ready to go in 1931, and would have preceded similarly themed, and very successful, gangster pictures “The Public Enemy” and “Little Caesar” in theaters, except for protracted wrangling with the Hayes Code office over the moral stance the film took with regards to its criminal protagonist, and whether or not Paul Muni‘s character (as well as George Raft and Boris Karloff in support, and Karen Morley as his moll) contributed to a “glamorization” of the gangster lifestyle. Hawks eventually squeaked by in states where the code was less strictly enforced by tweaking the ending and adding opening text that hammers the point home, along with the subtitle “Shame of the Nation.” Spin forward half a century, and Brian De Palma’s splashy remake positively wallows in its unabashed glamorization of gangsterism to the point that its archness is unmistakable, with the director achieving something of an apotheosis of his slick, visceral style, providing Al Pacino with the choleric, coked-up counterpoint to his more cerebral Michael Corleone, and launching Michelle Pfeiffer‘s career all at once (check out our full De Palma retrospective here).

Verdict: The two films show two auteur directors with very different sensibilities, styles, and contexts transforming the same material into two completely separate and individual movies, so we’re not even going to try to choose between them. Suffice to say, both are excellent, and if the cautionary satire of De Palma’s version is lost on the many rappers and fratboys who unironically embrace Tony Montana as an aspirational role model, it reflects poorly on the world, rather than on the film, if you ask us.

Bonus Round: An interesting stylistic Easter egg in the Hawks version: throughout the film, and usually when a character dies, somewhere in the mise en scene of the shot you can find a “X” shape, deliberately placed as a callback to the “X Marks the Spot” convention of the day in which photos of gangland murder sites often marked out where the bodies lay with an X. It’s particularly noticeable in the recreation of the St. Valentine’s Day massacre that happens in shadow beneath wooden support girders that are criss-crossed with X shapes.

Original: “Boudu Saved from Drowning” (Jean Renoir 1932)

Remake: “Down and Out in Beverly Hills” (Paul Mazursky, 1986)

In the right hands a remake can be like a good cover version of a favorite song — it transforms the material enough to give it new relevance and to feel like it brings new insight to bear, but it still honors the original. Paul Mazurksy‘s transposition of Jean Renoir‘s classic, about a tramp who overturns the lives of the affluent family who take him in (itself a take on a French play), from 1930s Paris to 1980s Los Angeles works so well because the framework is such that it allows some biting satire to occur at the expense of relatably new targets like the 1980s American yuppie, as opposed to the 1930s Parisian bourgeoisie. It is, of course, a great deal broader, and played for more outright laughs than the Renoir original, but Mazursky’s comedy still has intelligence and wit to burn, even if, overall, it comes across as more affectionate and lightweight. Renoir’s film, by contrast, is altogether darker. In fact, it’s still a surprisingly blackhearted watch, with Michel Simon‘s Boudu character representing a certain untamable, anarchic instinct that is not as easily categorized as the “lovable, gradually reforming rogue” that is the measure of Nick Nolte‘s ‘Beverly Hills’ character, Jerry. Boudu does not necessarily come to change his benefactors’ lives for the better, whereas Jerry ultimately does, and where Jerry is really a con man who manages to puppeteer his way into the household of arriviste couple Richard Dreyfuss and Bette Midler, along with their comely Mexican maid (the late Elizabeth Pena) and totally scene-stealing dog, Boudu warps the people around him to his own ends, but without really ever affecting any level of actual interest in them.

Verdict: “Boudu Saved from Drowning” is an anointed classic, though we’d say not quite as essential a comedy of manners as Renoir’s “The Rules of The Game,” for example, and it could now be a bit of a slog for first-time viewer unaccustomed to the sometimes silent-movie-esque theatrics, and the enormous, divisively cantankerous Michel Simon performance. Mazursky’s “Down and Out in Beverly Hills” is a frothy and fun watch, though it loses something of the sting of the original, particularly in its closing scenes, which could almost be interpreted to have the opposite moral from the original. So, neither film is flawless, but both are fascinating in their way.

Bonus Round: A third version exists here too, with Gerard Depardieu seemingly perfectly cast as the tramp character in 2005 French-language remake, “Boudu.” Sadly, it’s a film that goes the warm and life-affirming route, rather than the scabrous misanthropy of the original, and lacking even a particularly new setting or culture to lampoon it feels peculiarly pointless.

There are many other pairings we could have chosen, and we may do it again at some point. Most cinephile-y is the little-known fact that both Jean Renoir and Akira Kurosawa (who each appear elsewhere on this list) directed versions of Maxim Gorky‘s play, “The Lower Depths,” but since Kurosawa’s later film is directly based on the play and not, apparently, on Renoir’s film, we ruled it out. And as for Kurosawa’s “The Seven Samurai” being remade into John Sturges‘ “The Magnificent Seven,” that feels a little better known than most of the picks above. Elsewhere, depending on where you stand on classifying James Cameron as an “auteur,” “True Lies” is a remake of french action comedy, “la Totale!“; Matt Reeves‘ “Let Me In” is a remake of Tomas Alfredson‘s “Let the Right One In“; Cameron Crowe‘s “Vanilla Sky” is a remake of Alejandro Amenabar‘s “Open your Eyes“; Martin Scorsese famously remade the “Infernal Affairs” trilogy into “The Departed,” to Oscar-winning effect; while classic Western maven Henry Hathaway‘s “The Sons of Katie Elder” being remade as “Four Brothers,” and Delmer Daves‘ “3:10 to Yuma” being reworked by James Mangold, are just two of the many examples the Western genre has to offer. Let us know what you think of our takes on the above, and which other cinephile-y titles/remakes you’d like to see us cover in the future.

–Jessica Kiang and Oli Lyttelton

Miller\’s Crossing also owes a lot to Yojimbo.

Last Man Standing is not a remake of Yojimbo. Yojimbo and Last Man Standing are adaptations of the book Red Harvest. Sure it\’s nit picking but you made the caveat clear with your Maltese Falcon point.

What about True Grit and/or the Lady Killers?

Maybe they don\’t think Mel Brooks and William Friedkin are auteurs. Or Stephen Soderburgh since they missed Oceans 11.

How about both \’To Be or No To Be\’ on this list?

I think Wages of Fear and Sorcerer def deserved to be on this list.

Miller\’s Crossing also owes a lot to Yojimbo.